In celebration of UCLA’s first 100 years, we’re traveling back to our early days to visit some of the people, places and moments in time that have had a lasting impression on who we are as a university.

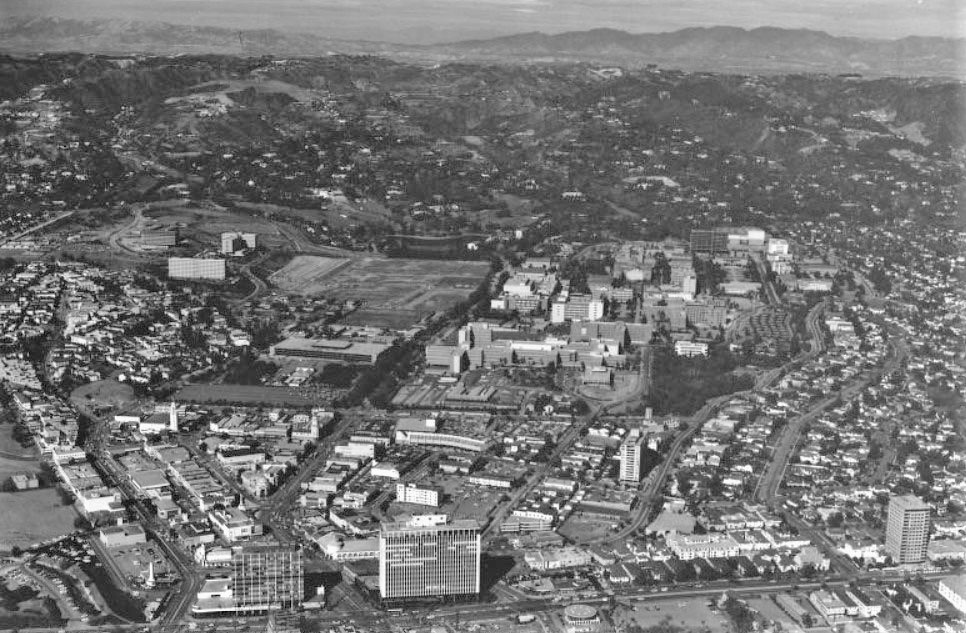

Westwood 1966

The sixties shook the nation — a war in Vietnam, political assassinations on American soil, a fight across the country for civil rights and huge strides in science, sending men into space and the first words across the internet. Bruins today walk in the footsteps of the progress made during a time when UCLA students refused to accept the status quo, staging protests and sit-ins, blazing a path in search of a more just and equitable world.

The turmoil would bring about change, as students continued pressing forward. Over the events of the decade, both celebratory and challenging, UCLA found a voice for justice, and began to create a community where diverse voices were respected and protected. Amid the politics and changing times, campus continued to grow. New buildings brought people together, athletic teams scored major victories, opportunities arose to recognize diverse points of view and in a room in Boelter Hall, scientists took a first step towards changing the world.

THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT COMES TO CAMPUS

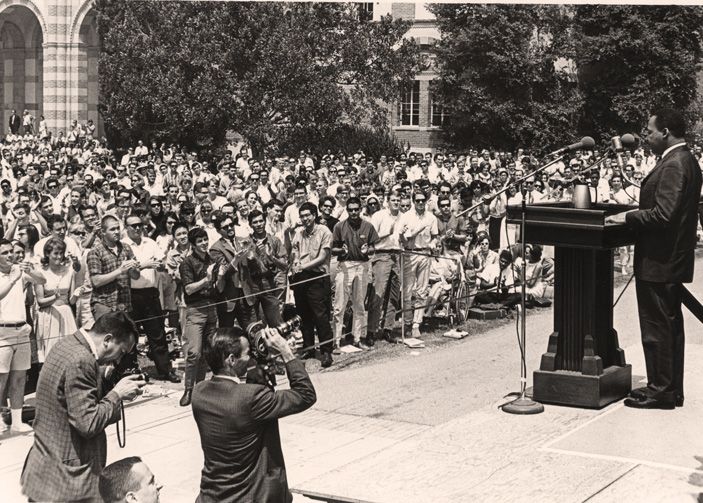

During the 1960s, students were engaged in the political discourse as an array of world leaders came to UCLA to share their ideas. President Lyndon B. Johnson, Mexican President Adolfo Lopez Mateos, Louis Lomax and columnist William F. Buckley, future Presidents Richard Nixon and John F. Kennedy, Emperor of Ethiopia Haile Selassie, writer and leader of the Black Panthers Eldridge Cleaver, and former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt all spoke on campus.

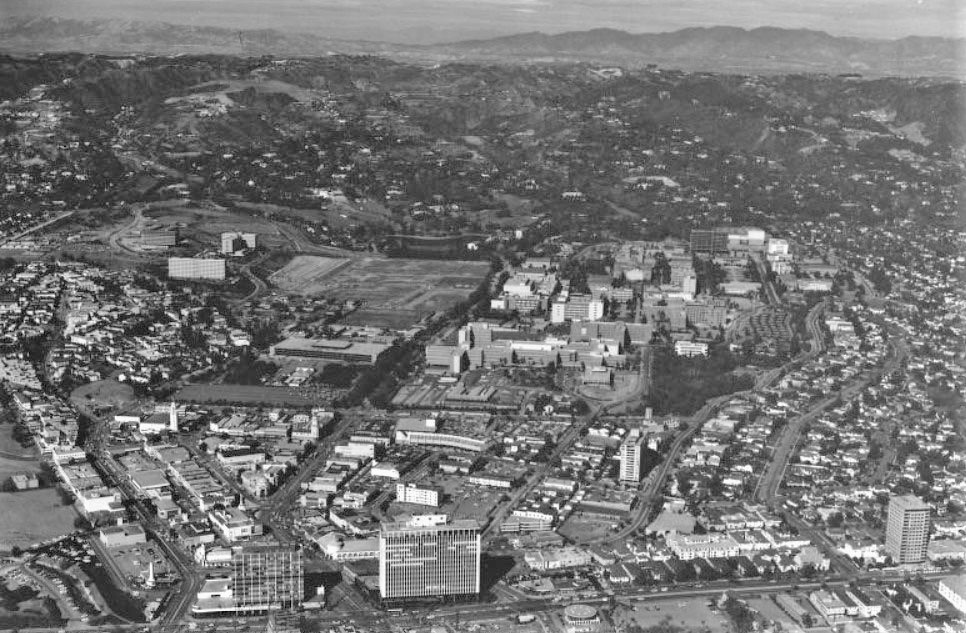

In April, 1965, just one month after his march from Selma to Montgomery, Martin Luther King Jr. came to UCLA in anticipation of passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. More than 5,000 gathered to listen to him speak about the need for racial integration, end of segregation, increased educational opportunity and guaranteed voting rights. King’s march for voting rights was depicted in the award-winning film “Selma,” directed by Ava DuVernay ’95, the first black female director to be nominated for an Academy Award for Best Picture.

In April, 1965, just one month after his march from Selma to Montgomery, Martin Luther King Jr. came to UCLA in anticipation of passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. More than 5,000 gathered to listen to him speak about the need for racial integration, end of segregation, increased educational opportunity and guaranteed voting rights. King’s march for voting rights was depicted in the award-winning film “Selma,” directed by Ava DuVernay ’95, the first black female director to be nominated for an Academy Award for Best Picture.

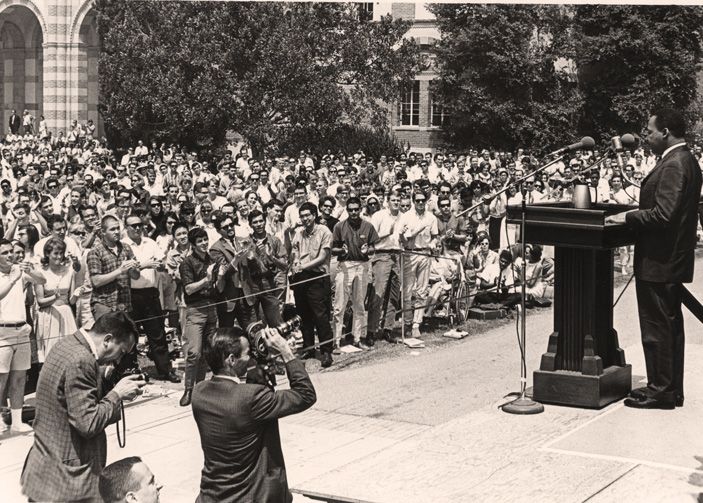

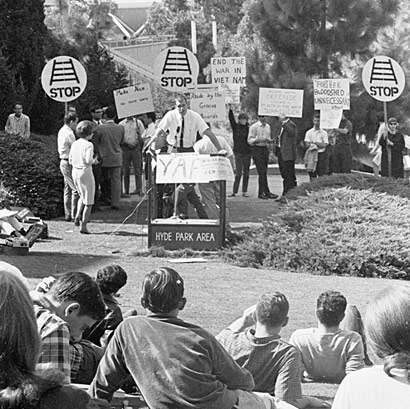

As the decade progressed, students joined the Free Speech movement sweeping the country. UC campuses designated areas for public expression. UCLA’s first space, “Hyde Park” near Janss Steps, saw protests, celebrations and performances. In 1966, it moved to a grassy knoll between Kerckhoff and Bruin Walk, and was renamed Meyerhoff Park in memory of philosophy professor and activist Hans Meyerhoff ’36, M.A. ’38, Ph.D. ’42.

As the decade progressed, students joined the Free Speech movement sweeping the country. UC campuses designated areas for public expression. UCLA’s first space, “Hyde Park” near Janss Steps, saw protests, celebrations and performances. In 1966, it moved to a grassy knoll between Kerckhoff and Bruin Walk, and was renamed Meyerhoff Park in memory of philosophy professor and activist Hans Meyerhoff ’36, M.A. ’38, Ph.D. ’42.

Chancellor Murphy was also central to making the Inverted Fountain the icon it is today. Tasked to design an innovative piece, Howard Troller and Jere Hazlett created a modern vision of Yellowstone Park’s natural beauty. Unlike a traditional fountain, water sprays from the edges, across stones then falling into a central hole. Since its completion in 1968, the fountain has become part of campus tradition — first-year students are Bruintized during orientation, but are warned that to touch the water again before graduation will add time to their academic career.

Chancellor Murphy was also central to making the Inverted Fountain the icon it is today. Tasked to design an innovative piece, Howard Troller and Jere Hazlett created a modern vision of Yellowstone Park’s natural beauty. Unlike a traditional fountain, water sprays from the edges, across stones then falling into a central hole. Since its completion in 1968, the fountain has become part of campus tradition — first-year students are Bruintized during orientation, but are warned that to touch the water again before graduation will add time to their academic career.

Musicians came too, many with a political message to share. Folk music band The Kingston Trio recorded their "College Concert," live at UCLA. South African singer and civil rights activist Miriam Makeba, jazz pianist Thelonius Monk with tenor saxophonist Charlie Rouse, jazz trumpeter Louis Armstrong and Andy Williams and the Christy Minstrels all performed on campus in the mid-sixties as did the "King of Calypso," Harry Belafonte. In 1964, The Beach Boys took the cover image for their Don’t Worry Baby/I Get Around 45 on Janss Steps.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. speaking from Janss Steps.

Dr. King encouraged students to engage with the social justice movement, and in his hour-long speech, the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize recipient appealed to students to join his Summer Community Organization and Political Education (SCOPE) program. That summer, 18 UCLA students traveled to the South to register people to vote. Among them were Daily Bruin staffer Neil Reichline, who decided to make the trip while listening to Dr. King, and Willy Leventhal, who was jailed along with 11 others for trying to integrate a church.

Hyde Park, later renamed Meyerhoff Park.

WESTWOOD EXPANSION

Other changes were taking place on campus as well during what would be the biggest building boom in UCLA history. Franklin Murphy served as chancellor for this expansion. Murphy, who became chancellor in 1960, would elevate UCLA to great prominence — creating research centers and adding iconic landmarks to the campus landscape. UCLA's Long Range Development Plan of 1963, presided over by architect Welton Becket, anticipated student enrollment would reach 27,500. While construction in the 1950s was fueled by tax surpluses from World War II, as this money ran out, three bond issues would provide UCLA with $95,000,000 in funds. The California Master Plan for Higher Education was signed into law in 1959, defining roles for the University of California system and increasing UCLA’s autonomy.

Driven by the belief that art should be enjoyed as a part of daily life, Murphy said, “There cannot be beauty of spirit without beauty of environment.” He championed the creation of a five-acre sculpture garden on the site of a former parking lot. Supervising architect Ralph D. Cornell designed the garden itself as art, with curving pathways that wind through expansive lawns, creating a space for study and reflection. Dedicated as the Franklin D. Murphy Sculpture Garden, the sculptures feature works by many of the great artists of the twentieth century, including Isamu Noguchi, Deborah Butterfield, Alexander Calder, Barbara Hepworth, Henri Matisse and Auguste Rodin.

Inverted Fountain

Construction required more buildable space, so Westwood Boulevard, which ran through the center of campus, was cut off from Sunset Boulevard. New buildings sprung up, including the Charles E. Young Research Library, a classic piece of mid-century modern architecture by A. Quincy Jones; Boelter Hall, home to an important discovery at the end of the decade; three high-rise residence halls, Sproul, Rieber and Hedrick, to accommodate the postwar baby boom; the concrete and steel Knudsen Hall of physics; the UCLA Museum of Cultural History, now the Fowler Museum, with an impressive permanent collection; six additional parking structures and Ackerman Student Union.

Ackerman Student Union

The Sunset Canyon Recreation Center was championed by former UCLA pole vaulter and vice chancellor Norman Miller ’39, as a place to build community outside the classroom. The Center opened in 1966 as students enjoyed the swimming pools, picnic areas and outdoor amphitheater. Miller played a part in many UCLA athletic advances, including coordinating UCLA’s involvement in the 1984 Olympic Games.

BRUIN INNOVATION

With a new building and an expanded program, the UCLA Medical Center continued to grow its reputation as a trailblazing center of excellence. In the early 1960s, UCLA surgeons were at the forefront of medicine, performing a historic parent-to-child kidney transplant, among the first in the United States. Today, the UCLA Kidney Transplant Program is one of the most active and innovative programs in the nation, performing 363 kidney transplants in 2017 and more than 8,000 in all.

The sixties saw the medical school and hospital double in size, with Dean Sherman Mellinkoff, M.D., overseeing unprecedented growth. By decade's end, the school had added a School of Dentistry, School of Public Health, School of Nursing, the Reed Neurological Research Center and the Jules Stein Eye Institute. Hollywood agent and doctor Stein and his wife hoped to prevent blindness by improving vision research and care. They pledged $1.25 million towards the $6-million construction, UCLA’s largest private grant at the time. The five-level building, designed by Welton Becket and Associates, would serve 2,000 patients each month.

The sixties saw the medical school and hospital double in size, with Dean Sherman Mellinkoff, M.D., overseeing unprecedented growth. By decade's end, the school had added a School of Dentistry, School of Public Health, School of Nursing, the Reed Neurological Research Center and the Jules Stein Eye Institute. Hollywood agent and doctor Stein and his wife hoped to prevent blindness by improving vision research and care. They pledged $1.25 million towards the $6-million construction, UCLA’s largest private grant at the time. The five-level building, designed by Welton Becket and Associates, would serve 2,000 patients each month.

Jules Stein Eye Institute

UCLA’s investment in the sciences led to other advances as well. In 1960, the UCLA physics workshop constructed a spiral ridge cyclotron and a biomedical cyclotron in 1969, advancing medical imaging and diagnosis. UCLA's Human-Machine-Environment Engineering Laboratory, led by professor John Lyman, became a leading center for developing artificial limbs. Lyman then developed a space technology curriculum for future astronauts and rocket designers. Physics major Walter Cunningham ’60, M.A. ’61, was the first Bruin in space. He and fellow astronauts spent 11 days aboard Apollo 7, the first manned Apollo mission.

Chemist Willard Libby became the first UCLA professor to win the Nobel Prize for his role in developing the process of radiocarbon dating. Archaeology, geology, geophysics and other sciences rely on radiocarbon dating for age determination; his work revolutionized these academic fields. In 1962, Libby became the founding director of UCLA’s Space Physics Center.

In 1965, future UCLA professor Julian Schwinger, along with colleagues Richard Feynman and Shin'ichirō Tomonaga, earned the prize for their theory of Quantum Electrodynamics, the pillar for quantum field theories. Schwinger joined the UCLA faculty in 1972 and continued his work on source theory until his death in 1994. In 2014, a transformative gift from his estate established a graduate fellowship in the department of physics and astronomy, enabling them to attract the world's best students.

Professor Leonard Kleinrock reenacts working with ARPANET.

THE GOLDEN AGE OF ATHLETICS

In 1963, with the athletics department in the red, Chancellor Murphy brought on J.D. Morgan ’41 to oversee the program. In a change, Morgan would report directly to the chancellor, instead of to the Associated Students of UCLA (ASUCLA). In his 16 years as UCLA’s director of athletics Morgan turned the finances around, but is best remembered for the 30 NCAA championships Bruins won during his tenure. The home of UCLA Athletics was formally dedicated The J.D. Morgan Center in his honor in 1984.

The Alumni Association, under the leadership of William Forbes ’28, UCLA’s 1967 Edward A. Dickson Alumnus of the Year, led a successful fundraising campaign to build the new Pauley Pavilion as UCLA’s home court. Drake Stadium and Spaulding Field were also both added to campus, expanding the possibilities for Bruin athletics.

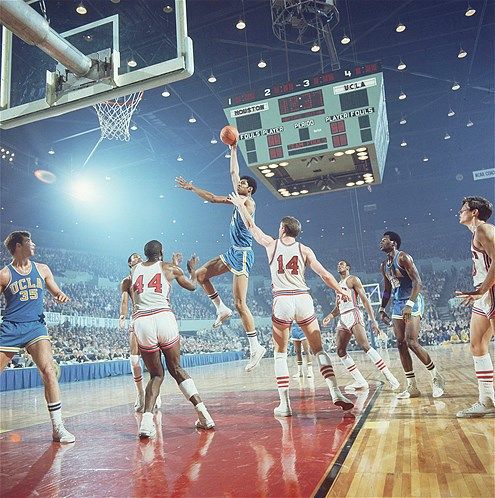

Coach John Wooden’s first NCAA Championship in 1964.

Regarded as one of the best NBA players of all time, Abdul-Jabbar led the Bruins to three national championships and was a three-time All American. Still the league's all-time leading scorer, he led the Lakers to five championships in 14 years and blocked more shots than any player in NBA history. He was named the Greatest College Player of All Time. Abdul-Jabbar is a writer and tireless advocate for civil rights. In 2016, President Obama awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar (then Lew Alcindor) playing against the University of Houston.

UCLA track and field star Winston Doby ’63, M.A. ’72, Ed.D. ’74, would become UCLA vice chancellor for student affairs. Doby spent his career emphasizing community outreach to encourage minority students and those from low-income families to attend UCLA.

Tennis star Arthur Ashe ’66, who came to UCLA on a tennis scholarship, became the first African‐American man to win Wimbledon and the U.S. Open, and to be ranked No. 1 in the world. As an activist and tennis champion, Ashe used his platform to fight against racial segregation in South Africa and raise awareness of the AIDS epidemic. Ashe also worked to inspire young people to take up the sport he loved. The Arthur Ashe Student Health & Wellness Center was named in his honor.

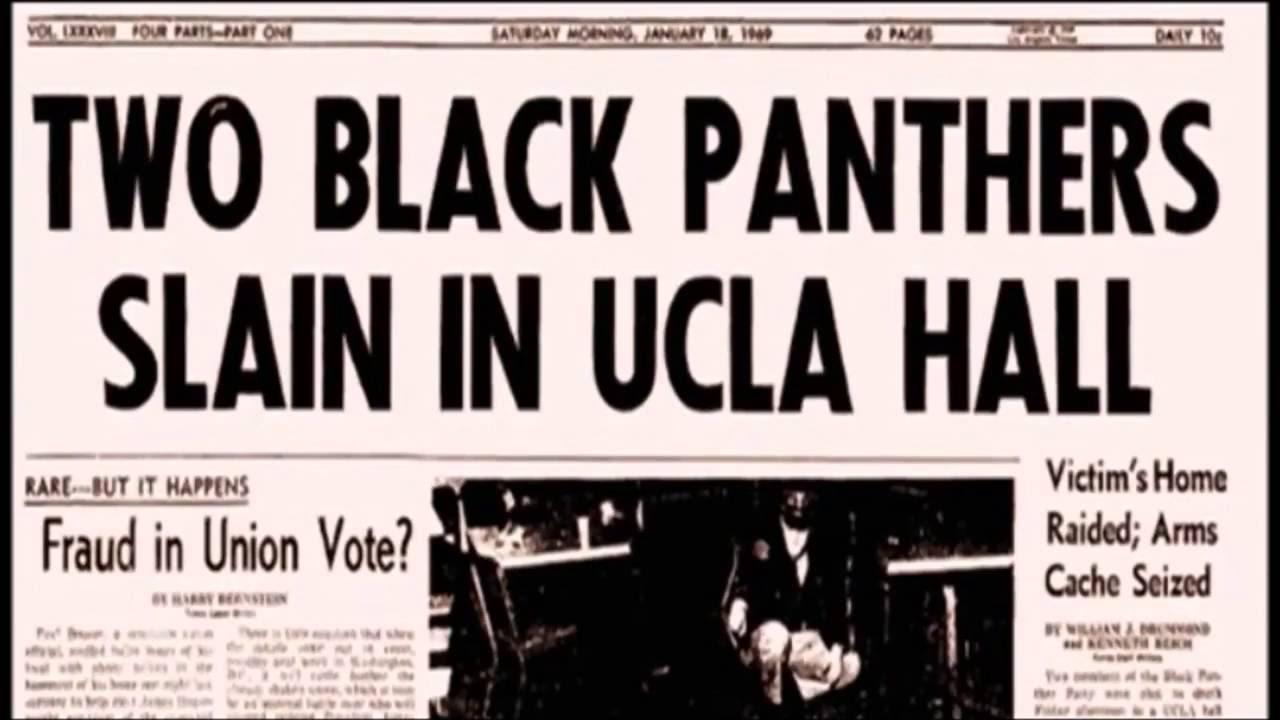

THE FIGHT FOR DIVERSITY AND EQUITY ON CAMPUS

While UCLA has always been an integrated school, the majority of faculty and students had been white. In the sixties, a movement began among the community to campaign for greater diversity. The establishment of UCLA’s prestigious ethnic studies programs were a step forward towards today’s collective commitment to a deep appreciation of the university’s many cultures and experiences.

When Dr. King spoke to students at the base of Janss Steps, he told the gathered crowd, “If democracy is to live, segregation must die.” Later that year California passed Proposition 14, nullifying the Rumford Fair Housing Act, which sought to end racial discrimination by landlords. The UCLA chapter of the Delta Sigma Theta sorority, dedicated to public service among the African American community, worked to defeat the proposition. Some consider Prop. 14, and the underlying issue of residential segregation, among the causes of the Watts Rebellion of 1965. The bill was later declared unconstitutional by the California Supreme Court.

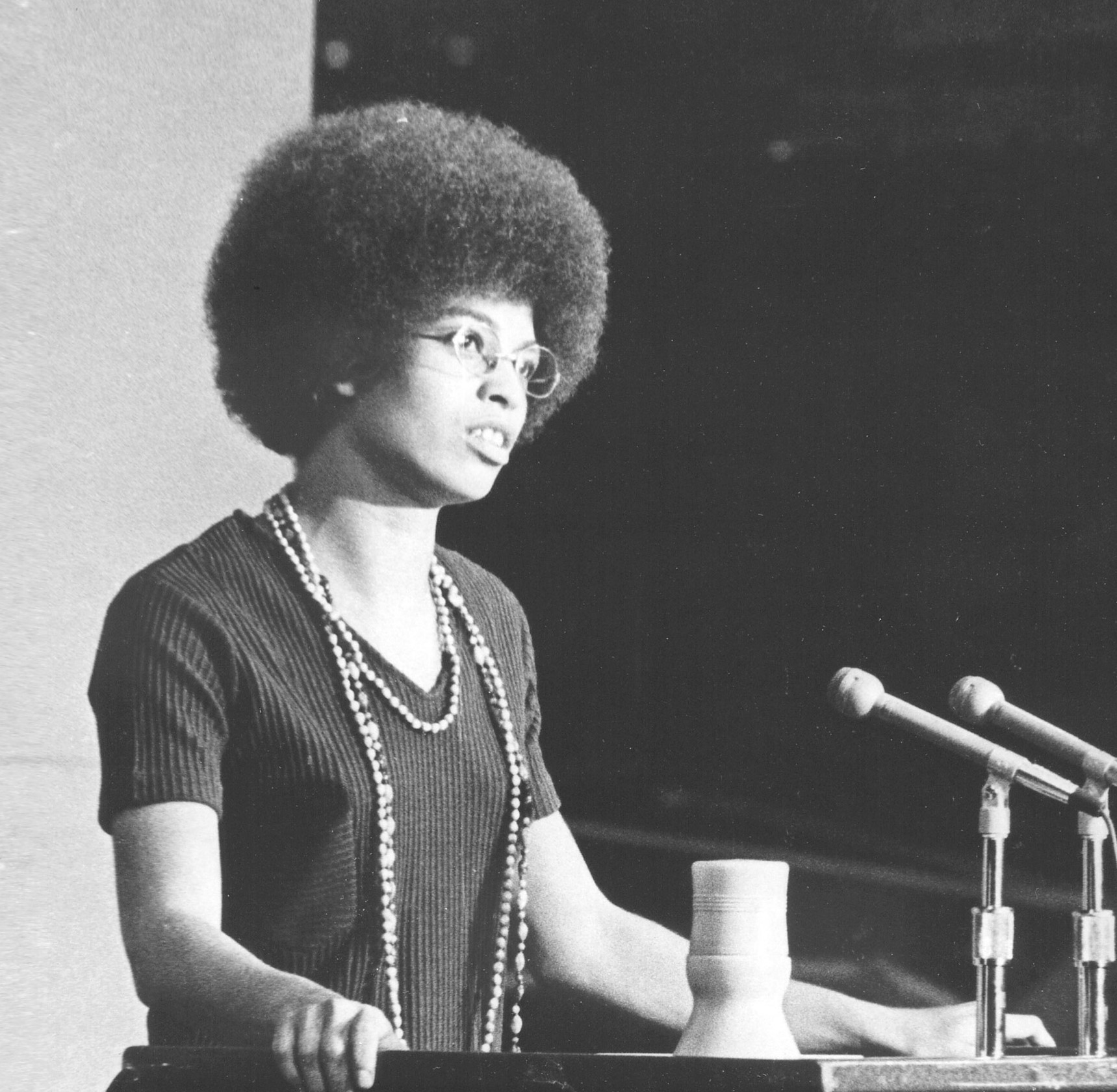

Carolyn Webb, Homecoming Queen in 1968

In the 1960s, minority enrollment at the university was around 12%, with many minority and women students achieving individual success, but often feeling marginalized as a group. Willette Murphy Klausner ’61 was the first woman elected senior class president. Featured in the "college issue" of Mademoiselle, Klausner became the first African American to appear in an American fashion magazine. Training to be a teacher, Linda Alvarez ’63 became the first Latina to anchor a weekday newscast for an English-language TV station in Los Angeles.

Inspired by events such as this, students began work to establish a tradition of tolerance and acceptance. Five Asian-American students — Mike Murase, Dinora Gil, Laura Ho, Tracy Okida and Colin Watanabe — started a newspaper, Gidra, to represent their experiences. In 1966, African American students founded Harambee, renamed the Afrikan Student Union (ASU), to advocate for UCLA students of African descent. The UCLA Black Alumni Association (UBAA) was established in 1968, inspired by efforts to organize alumni of color by leaders such as former Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley ’41 and UCLA Vice Chancellor emeritus Winston Doby. UBAA’s vision is to achieve and maintain equality by unifying UCLA’s African American alumni, students, faculty and community members. UBAA received the 2018 UCLA Award for Network of the Year in celebration of the 50th anniversary of service to the UCLA community.

Student groups protesting lack of representation on campus, came together to campaign for the creation of the Institute of American Cultures (IAC) to reflect the presence, history, and contributions of underrepresented groups on campus. Four student-led curriculum and research centers, among the first of their kind, were established in 1969 — the Chicano Studies Research Center (CSRC), the Ralph J. Bunche Center for African American Studies, the Asian American Studies Center and the American Indian Studies Center.

The centers enrich the university by contributing to the understanding of diverse cultural experiences. Each is home to important archives, research libraries and internationally renowned publishing efforts. In 2019, during UCLA's centennial, the centers will mark their 50th anniversary of expanding understanding of the value of diverse cultures. The IAC and the four centers continue to work for academic freedom, civil and human rights, and community activism.

Dr. Robert Singleton, M.A. ’62, Ph.D. ’83, became the founding director of the Ralph J. Bunche Center for African American Studies. A civil rights activist, Singleton had been a Freedom Rider, using nonviolent resistance to protest segregation. He was part of a diverse group of UCLA students who traveled south to join others riding buses to test a Supreme Court ruling outlawing segregation. Singleton, his wife, Helen, and members of the group returned to UCLA in 2015 to tell their stories and be honored for their history-making contributions towards equal rights.

Angela Davis returns to UCLA after being dismissed.

Dinners for 12 Strangers began in 1968 as a way to unite the Bruin community during a time of civil unrest. The first year, two dinners brought faculty, students and alumni with diverse viewpoints together for a meal and conversation in search of common ground. Organized by Alumni Affairs, this past year alumni hosted more than 500 dinners around the world involving more than 3,700 Bruins.

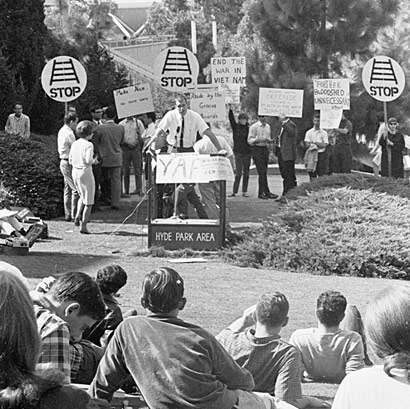

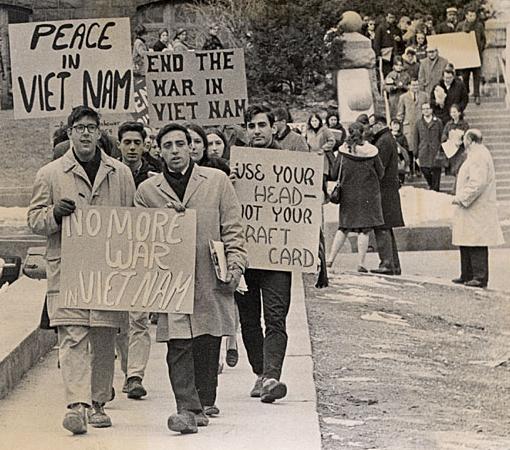

ANTI-WAR UNREST

with Ralph Bunche.jpg)

Ralph Bunche ʼ27 with Chancellor Charles Young (right)

Students protesting the Vietnam War.

As the decade came to a close, UCLA celebrated its 50th anniversary. In its first 50 years the university had been transformed from a two-year teacher’s college into an internationally respected institution. The next 50 years would build on these accomplishments, inspired by past achievements, and setting the stage for future generations.

Series Archive