In celebration of UCLA’s first 100 years, we’re traveling back to our early days to visit some of the people, places and moments in time that have had a lasting impression on who we are as a university.

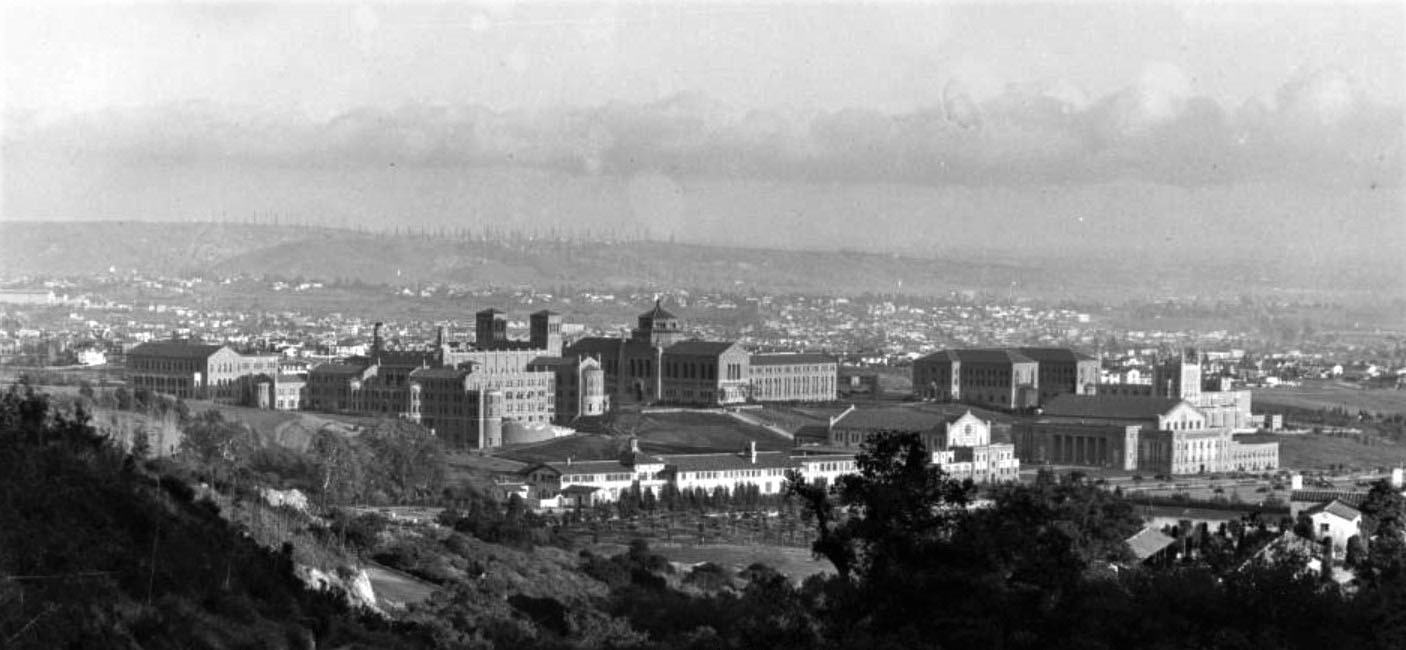

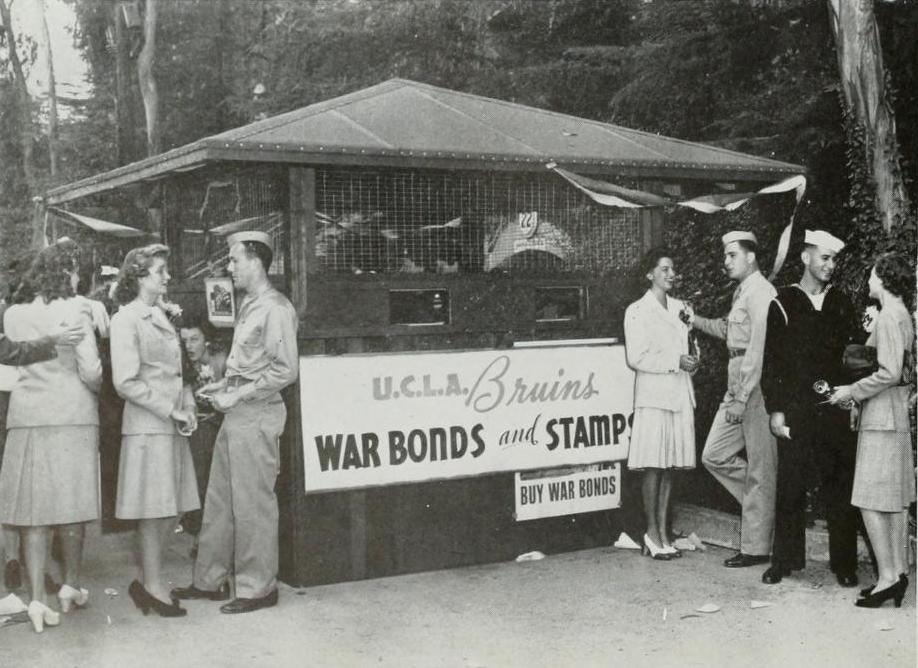

Entering its third decade, UCLA had transformed from a two-year teachers’ college into a full-fledged university set on a hilltop in the midst of a growing city. The decade would be defined by forces far beyond the school’s campus, as the United States entered World War II, an event that would touch every aspect of life at UCLA. As always, UCLA would rise to the occasion, emerging from the decade stronger and more determined than ever to create a better world for all.

Mayor Tom Bradley

UCLA Coast Artillery Unit

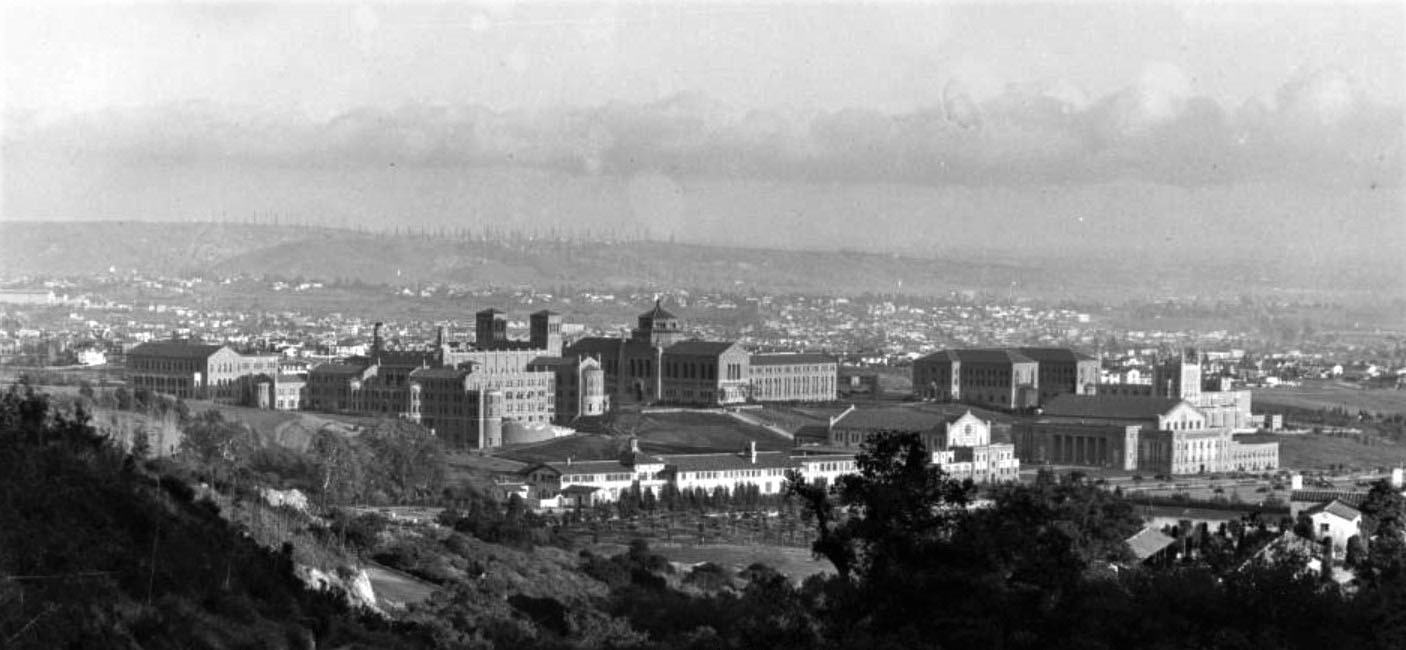

Robert Conrad killed at Pearl Harbor

More than 6,000 members of the UCLA community served in World War II, and 260 students, faculty and alumni were killed. Among them was Seaman 2nd Class Robert F. Conrad, a member of UCLA’s Coast Artillery Unit. Conrad was at Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, and was killed in the bombing of the battleship USS Arizona.

Dorothy Nichols died transporting a fighter plane.

Hitoshi “Moe” Yonemura, a popular Yell leader killed in the war.

On the 50th anniversary of the mass removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans, Yamazaki was awarded her bachelor’s degree in dietetics. In May 2010, UCLA honored all affected students with special honorary degrees inscribed, “to restore justice among the groves of the academy.”

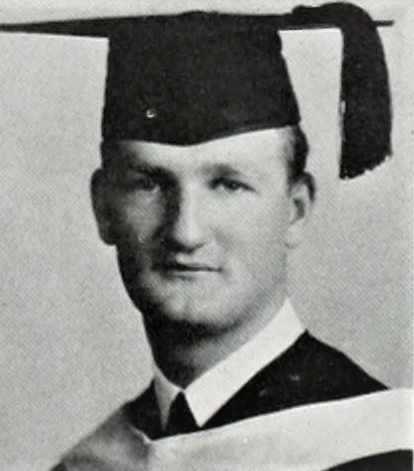

Selling War Bonds and Stamps to the crowds at the football game, 1944

The Victory Bell

In 1944, a competition between fraternities began a tradition as they competed to be named the “Champion Serenaders of Sorority Row.” In 1945, ASUCLA director William Ackerman ’24 arranged a co-ed singing contest held in Royce Hall called Spring Sing. The winners’ albums were distributed with yearbooks and sold in the student store. Today the popular annual event, hosted by the UCLA Alumni Association and Student Alumni Association, draws a crowd of over 8,000 to Pauley Pavilion to hear UCLA’s most talented students perform.

Following the war, UCLA embarked on a $38 million construction program, the largest campus project in America at the time. Several of UCLA’s premier graduate schools were established during this period — including funding and building the engineering, nursing, law and medical schools. In 1945, Clarence A. Dykstra, a professor of political science and an advocate for on-campus housing, became UCLA’s first post-World War II provost. Dykstra reversed a regental policy to establish UCLA’s first dormitories. UCLA’s Dykstra Hall opened in 1959 and was the first co-ed residence hall in the country.

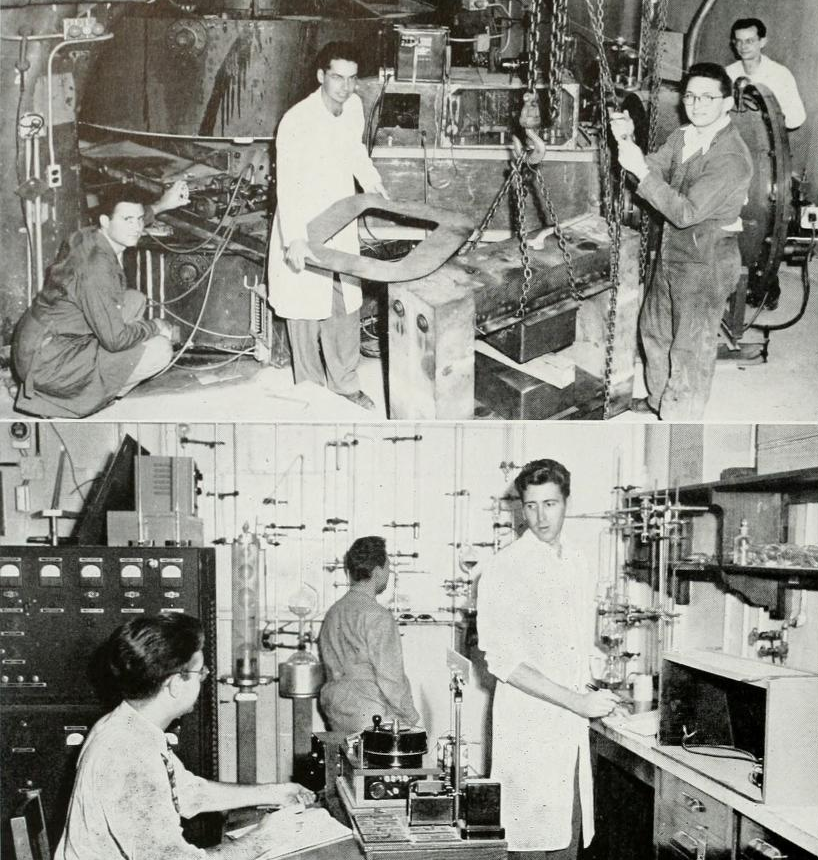

The aerospace work at UCLA during the war showcased the need for a college of engineering. The UCLA Alumni Association spearheaded a successful drive for the school, petitioning former Alumni Association president and Lieutenant Governor Frederick Houser ’26 to sponsor a funding bill. The School of Engineering, now the Henry Samueli School of Engineering and Applied Science, was established in 1944 and classes began in 1945 with 379 students under the leadership of Dean L.M.K. Boelter. The school grew quickly, acquiring a modern electron microscope and moving into a new building. Barbara Wynn Pritzkat ’48 was among the first graduates and the first female graduate. Pritzkat went on to work for Northrop in the aircraft industry, later earning a certificate in archaeology from UCLA Extension.

The aerospace work at UCLA during the war showcased the need for a college of engineering. The UCLA Alumni Association spearheaded a successful drive for the school, petitioning former Alumni Association president and Lieutenant Governor Frederick Houser ’26 to sponsor a funding bill. The School of Engineering, now the Henry Samueli School of Engineering and Applied Science, was established in 1944 and classes began in 1945 with 379 students under the leadership of Dean L.M.K. Boelter. The school grew quickly, acquiring a modern electron microscope and moving into a new building. Barbara Wynn Pritzkat ’48 was among the first graduates and the first female graduate. Pritzkat went on to work for Northrop in the aircraft industry, later earning a certificate in archaeology from UCLA Extension.

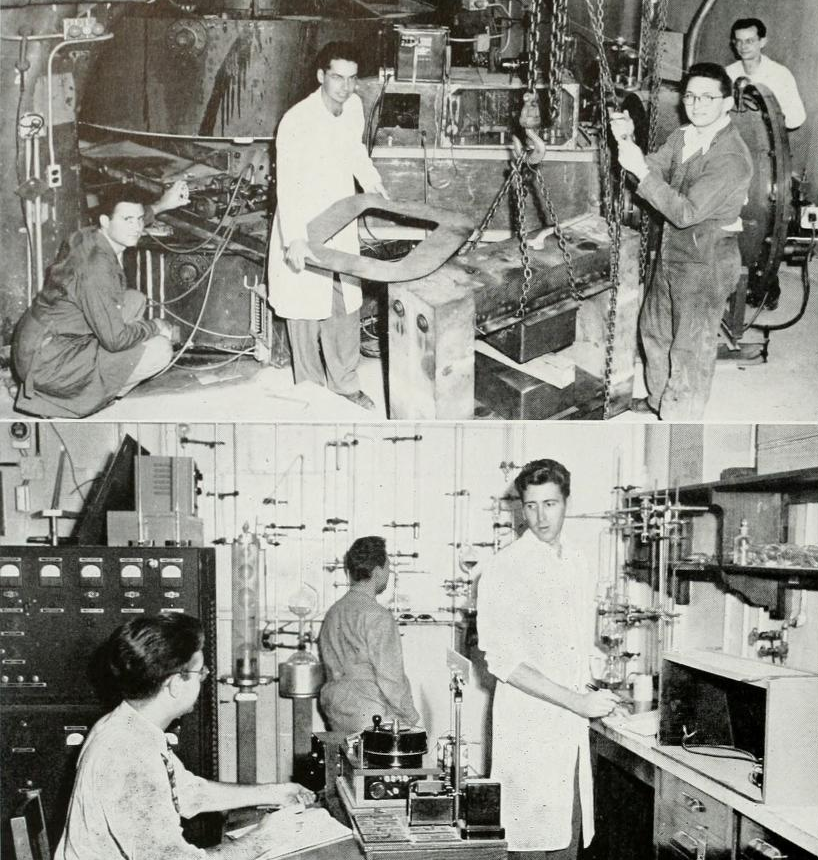

UCLA students using a cyclotron, 1949

In 1949, Gov. Warren (left) and UCLA’s first medical school dean, Stafford Warren, inspect the future site.

Bruin Nurses, 1950

In the 1940s, local Los Angeles politician William Rosenthal wanted to create an affordable, local alternative to the city’s private law schools. The UCLA Alumni Association and the State Bar of California got behind the idea. In 1947, Governor Warren authorized $1 million for the school’s construction. The UCLA School of Law opened in 1949 in former military barracks behind Royce Hall, becoming the first public law school in Southern California. UCLA Law soon became the youngest top-ranked law school in the United States.

As UCLA grew, the alumni finance committee proposed the UCLA Progress Fund to generate philanthropy for UCLA. Approved by the regents in 1943, the Progress Fund was the predecessor of the UCLA Foundation, which manages the resources generously donated towards advancing the university.

Officers of the Alumni Association, 1944

In the late 1940s, with the rise of fears of Communism on college campuses, members of the UC system were suspected of so-called un-American activities. In 1949, UC Regents required faculty and staff to disavow membership in the Communist Party and swear a loyalty oath. By 1950, nearly 100 faculty and staff had been dismissed for refusing to sign.

Coach Wooden in his first year as head coach of UCLA Men’s Basketball.

The 1940s were a time of great tragedy on the world stage, yet they were also a testament to a fighting spirit, honoring the sacrifices of many while forging ahead into the future. Many of our treasured UCLA traditions began during these years — Spring Sing, Mardi Gras, the battle for the Victory Bell and the annual Alumni Awards. UCLA also founded several world-renowned professional schools, including the UCLA School of Law, the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, UCLA Nursing School and the Henry Samueli School of Engineering and Applied Science. UCLA continued to gain an independent voice in the UC system, as alumni earned representation in the UC Board of Regents and established the Progress Fund to help ensure the financial longevity of the university. Each step forward has touched thousands of lives transforming them for the better.

UCLA would begin the 1950s with a renewed sense of enthusiasm. With an influx of students and a growing campus, UCLA was poised to enter the challenges and successes of a new decade.

Series Archive