In celebration of UCLA’s first 100 years, we’re traveling back to our early days to visit some of the people, places and moments in time that have had a lasting impression on who we are as a university.

In March of 1930, with UCLA’s first four buildings mostly in place, and much of the campus a construction zone, the new Westwood home of UCLA was dedicated by the UC Regents in the name of the people of California. The majestic buildings, in an Italian style, perched on a hill overlooking a vista of rolling plains that stretched to the ocean, dotted with haciendas and citrus farms.

Dedication ceremony – Outgoing UC President William W. Campbell (left) and Incoming President Robert G. Sproul, 1930

Registration - Students lined up at Royce Hall, 1930

In early April 1930, a film called “Bruin Review” screened in Royce Hall for a 35 cent admission fee. The 35mm film was financed and co-produced by Bud Graybill ’32, photographer for the Southern Campus who went on to work as a Hollywood movie photographer, and Thelner Hoover ’31, the official photographer for several UCLA publications, who took many of the aerial photographs of campus in the 1930s. “Bruin Review” featured a “chronological history of the development of UCLA from normal school days to the present time.” After graduation, Thelner Hoover married Louise Brown Hoover ’31, who served as vice president of the Alumni Association (1949-51). Hoover’s photos are part of the UCLA Historic Photographs collection, though only portions of the “Bruin Review” are known to exist.

Kerckhoff dedication in 1931

The student Co-op also moved from its temporary quarters into space in Kerckhoff. To celebrate the move, the Associated Student Union California organized a dance in what they called the “old shack.” Students tore down the walls in preparation and held the dance in the building’s shell, where “every student will be able to express his disdain of the little green building by stamping on its remains.”

Victory Flag

The West Los Angeles Rotary Club stepped up, and in February they formally presented the UCLA Victory Flag to the student body, accepted by ASUC President Earle Swingle ’31. The letters UCLA, in blue and gold, spanned a 12 by 31 foot flag, inscribed “symbolic of mighty triumph past, present and future.” This Victory Flag flew proudly for 18 years, replaced with one purchased through a fundraising campaign that encouraged students and alumni to toss loose change onto the worn out flag.

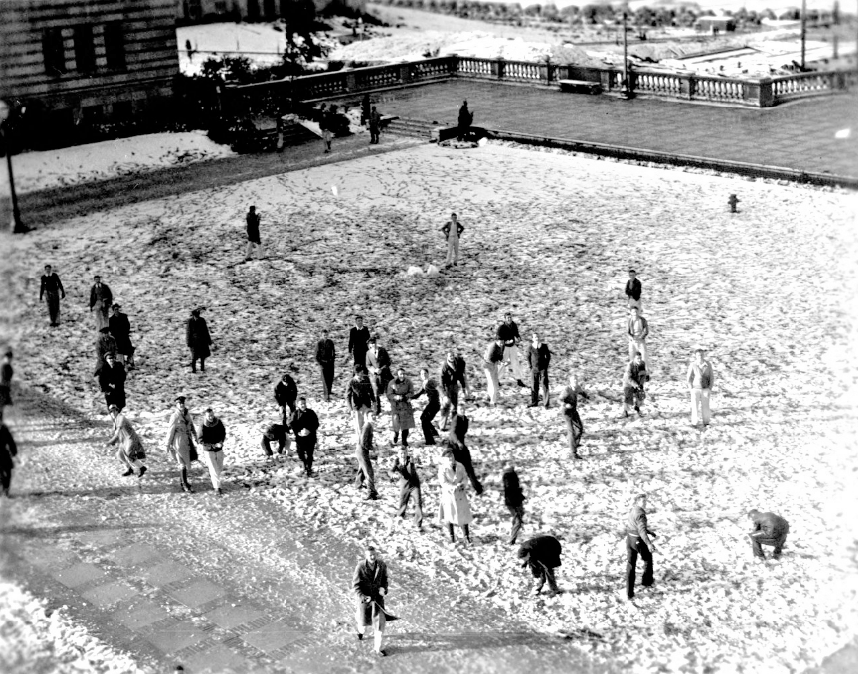

On a frosty January morning in 1932, after an unusually cold winter, the UCLA campus woke to a winter wonderland. Snow had fallen overnight, blanketing the campus in a layer of white.

Students, and some faculty members, made snowmen, while others celebrated with a big snowball fight on the quad. Luckily photographers Hoover and Graybill arrived in time to document the rare event, which melted away by the afternoon.

Students, and some faculty members, made snowmen, while others celebrated with a big snowball fight on the quad. Luckily photographers Hoover and Graybill arrived in time to document the rare event, which melted away by the afternoon.

Snowball fight in 1932

That summer, in the midst of the Great Depression, the 1932 Olympics came to Los Angeles. To afford the cost, the city decided to use existing buildings, and UCLA made its new Women's Gym available (now Glorya Kaufman Hall). UCLA hosted the Olympic Games on campus again in 1984, and is excited to host events again in 2028.

Along with Olympic athletes, in 1932, UCLA also hosted a lecture by Albert Einstein at Royce Hall, who spoke to enthusiastic students and faculty about his Theory of Relativity.

The Einsteins with Ernest Carroll Moore

The Class of ’33 would be the first to have an all-Westwood experience as trailblazers of the new campus. As the university settled in to life in Westwood, growing in size, resources and respect, UCLA petitioned the Regents to add graduate study programs. Frederick Hauser ’26, president of the Alumni Association, who went on to serve as Lieutenant Governor of California, and a council of alumni faculty and community leaders advocated for the addition. Hauser had a positive outlook, since the era’s economic conditions made it impossible for many students to go to Berkeley to continue their education.

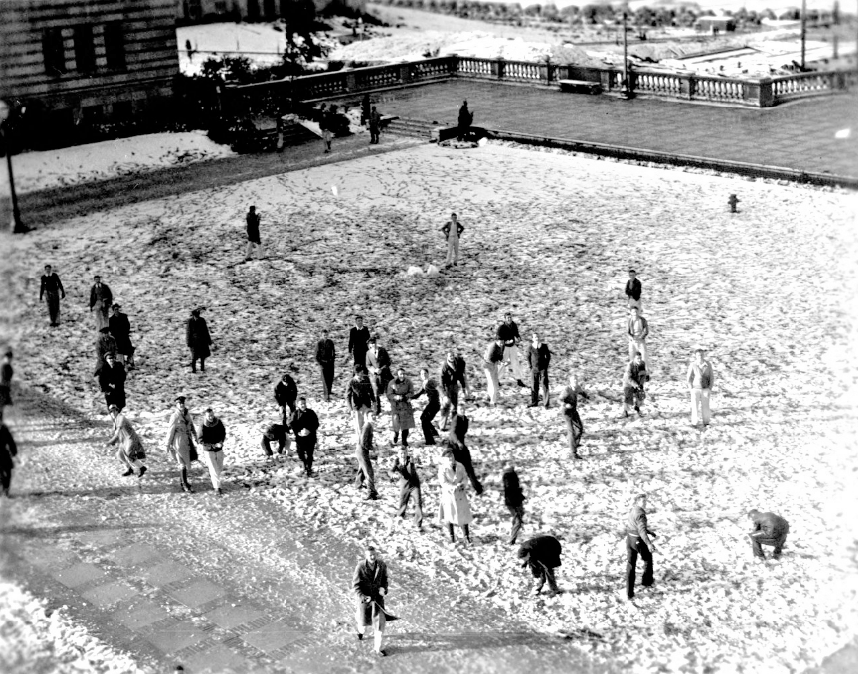

James LuValle in 1935

LuValle was also a counselor at UniCamp, which grew out of a Depression-era food drive by 11 students for families in West Los Angeles. Students wanted to do more to help, so they organized a summer camp, and welcomed its first campers to Big Pines in the San Bernardino Mountains in the summer of 1935. UniCamp continues to host children from underserved communities in Los Angeles.

UCLA Alumni Association grew during the 1930s as well. The Class of ’30 would be the first to graduate on the new Westwood campus. With a growing enrollment, membership in the Alumni Association grew as well to more than 2,400 strong. UCLA was originally formed as a Branch of the University of California at Berkeley, with Berkeley controlling the power and finances. In many cases, Berkeley would refuse to support UCLA initiatives, including the campaign to add graduate study.

In 1933 UCLA alumni joined with faculty and administration to petition Berkeley for their own association. They passed two resolutions, known as UCLA’s “Declaration of Independence,” stating that the board must be recognized as an autonomous body, and be given the power to make recommendations affecting the University as a whole.

In 1933 UCLA alumni joined with faculty and administration to petition Berkeley for their own association. They passed two resolutions, known as UCLA’s “Declaration of Independence,” stating that the board must be recognized as an autonomous body, and be given the power to make recommendations affecting the University as a whole.

Alumni Homecoming float in 1934

The UCLA Alumni Association gained official independence in 1934, establishing its own officers, council and constitution. The organization was an active force on campus, organizing the first Westwood homecoming, which also happened to be UCLA’s first conference football victory. One new initiative was to form regional clubs — Long Beach held the first regional meeting followed by one in San Francisco. By 1936, the Association was one of the five largest in the nation, and began to raise support for Alumni Scholarships. The first scholarships of $150 each were awarded to two graduates of California high schools.

Commencement Day

One impact of the Great Depression felt at UCLA, and among students around the world, was an interest among students in communism, socialism and isolationism. Several communist groups were formed on campus, with President Moore strongly opposed. Among other groups there was a branch of the Social Problems Club and an opposing group called the UCLA Americans. The University of California banned partisan politics on campus, leading large groups to gather on what was known as “Peace Hill,” on the far side of the Arroyo Bridge.

In October 1934, students tried to arrange for author-socialist Upton Sinclair, who was running in California's governor race, to speak on campus. When Celeste Strack, on behalf of the National Student League, a Communist-led student organization, filed a petition and was denied, she approached ASUC President John Burnside ’34. When UCLA President Moore discovered what was happening, he suspended Burnside, along with Strack and three other students — Mendel Lieberman ’35, Sidney Zsagri ’35 and Tom Lambert ’36 — for potentially assisting the National Student League in “destroying the university.”

The charges caused large student demonstrations and a great deal of publicity. Ultimately, the student leaders were reinstated and allowed to resume their official positions. Strack was not cleared until December, when she was academically reinstated after petitions, calls from other university student leaders and walk-out protests. Strack went on to work in social work and helped create the LA County Department of Children and Family Services.

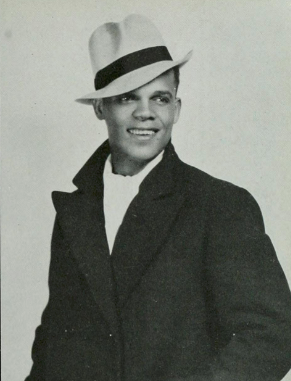

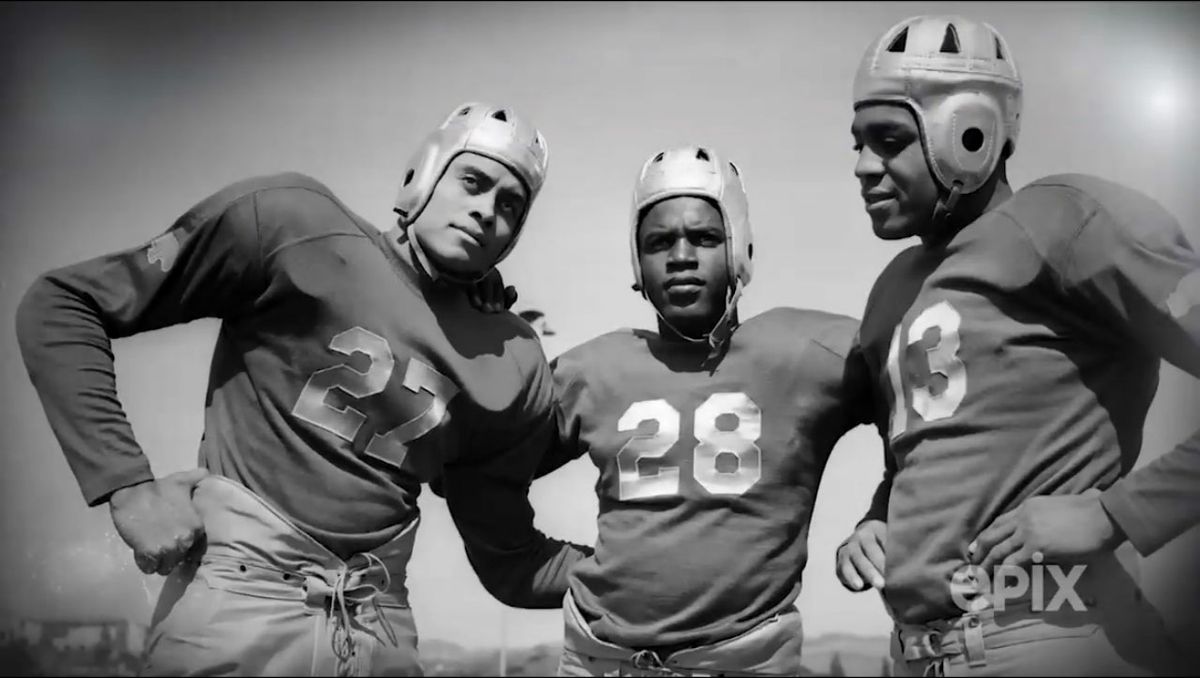

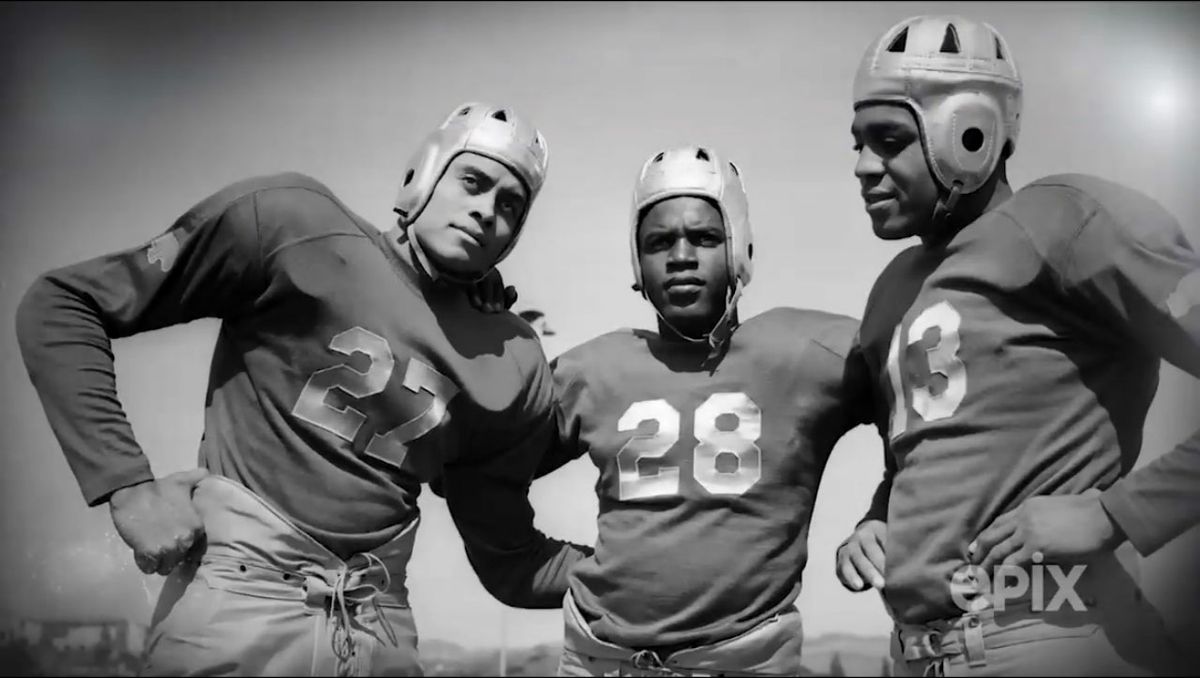

In 1939, UCLA had its first undefeated football season. Superstar athletes, Jackie Robinson, Kenny Washington ’41, and Woody Strode ’39 played for UCLA, along with teammate Ray Bartlett. With four black students on the roster, at a time when only a few African American students played college football, UCLA’s was the most integrated team in the league. Washington and Strode were two of the best-known college football players of the time. Washington was the first Bruin football player to be named an All-American and Strode also excelled as a track star and actor. When they graduated, the segregated NFL would not sign them. However in 1946, it was decided that since the LA Coliseum was supported with public funds, it was bound by law to be integrated. Washington and Strode joined the Los Angeles Rams, re-integrating the NFL after a 13-year ban on African-American players.

From left: Woody Strode, Jackie Robinson, Kenny Washington

Robinson lettered in four sports at UCLA: baseball, basketball, football and track. After serving in the Army, and playing baseball in the Negro League, Robinson was signed and started at first base by the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947, breaking what was known as the Major League Baseball “color line.” Robinson’s outstanding play, in the face of often hostile and racist crowds, earned him the first MLB Rookie of the Year Award, the National League Most Valuable Player Award and, in 1962, he was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. In 2016, UCLA dedicated a monument to Robinson in front of the John Wooden Center, with a plaque containing his memorable words, “A life is not important except in the impact it has on other lives.”

In 1939, the Alumni Association, now 5,000 members strong, gifted the UCLA student body with a Victory Bell. The almost 300-pound bell was an old locomotive bell, attached to wheels and brought to games, where UCLA cheerleaders rang it after the Bruins scored. The gift would spark a prank war between two rivals that would create long-lasting traditions.

As UCLA prepared to enter the 1940s, the Southern Campus yearbook referred to 1929 -1939 as the “Era of Progress.” Looking back, UCLA had established itself as an equal partner to UC Berkeley, no longer a branch of the northern campus. New fields of study, new campus buildings and graduate studies created more opportunities, and the student body continued to grow. Student walk-outs and demonstrations on Peace Hill foreshadowed the coming decades, as students found a growing voice. However, World War II would change everything in the coming decade.

Series Archive