|

UCLA has a deep history of African Americans who have made significant contributions to UCLA and beyond. As a sequel to last year’s Inspirational Black Bruins, this timeline highlights additional impactful events and individuals, whose story played a role on the growth of UCLA and whose influence can still be felt today. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A trailblazing scientist and an Olympic athlete, James “Jimmy” LuValle grew up in Los Angeles. He loved to read and had a library card before he started kindergarten, later working after school as a page at the L.A. Public Library. After high school he enrolled at UCLA to pursue a degree in chemistry. A Regent’s Scholar, considered friendly and outgoing, he worked his way through college as a laboratory assistant. Captain of the track and field team, he was nicknamed “Westwood Whirlwind.” He graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1936, winner of the Jake Gimball Award for outstanding all-around senior. One of the world’s fastest runners, he traveled to the 1936 Olympic Games in Nazi Germany, winning a bronze medal in the 400-meter event. Later that year, he returned to UCLA to pursue a master’s degree in chemistry and physics, and successfully advocated with the dean for a place on campus where all UCLA graduate students could congregate to socialize. Associate Graduate Students (ASG) was born, and LuValle became the first president. He received his M.A. in 1937, and went on to study under Linus Pauling at California Institute of Technology where he earned his Ph.D. After graduation, despite facing racial discrimination, LuValle went on to a successful career. He was hired to teach at Fisk University and later became the first black chemist to work for the Eastman Kodak research labs. His research on color photography earned him three U.S. patents. During WWII he worked at the Government Office of Scientific Research and Development. His legacy at UCLA includes the Professional Achievement Award from the Alumni Association and in 1985 the LuValle Commons was named in his honor. L.A.’s first, and only, African-American mayor, Tom Bradley ’41, spoke at the building’s dedication. Having followed in LuValle’s footsteps as a track star and student at UCLA, he called LuValle his inspiration in overcoming barriers to achieve his dream. |

|

|

In the 1940s many college football teams had no black players and those that did often adhered to an agreement to bench them when playing against segregated schools. UCLA did not adhere to this so-called “gentlemen’s agreement.” Superstar athletes, Jackie Robinson, Kenny Washington ‘41, and Woody Strode ‘39 played for UCLA and were one of the fiercest backfields in college football, leading UCLA to its first undefeated season in 1939. Washington and Strode were two of the best-known college football players in the nation. Washington was the first Bruin football player to be named an All-American, represented UCLA in the College All-Stars Game and also played baseball. Strode excelled as a track star and actor. Despite their obvious athletic dominance, the NFL was segregated and would not sign them to a team. Washington joined the LAPD, his uncle was the first African-American lieutenant in the Los Angeles Police Department. Strode joined the army. Both played in the African-American semi-pro football league instead. In March, 1946, one year before Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier, L.A.’s African-American print media informed the Rams’ owner that the LA Coliseum, supported with public funds was bound by law to be integrated, and the Rams would be in breach of their contract with an all-white team. Washington and Strode joined the Los Angeles Rams, re-integrating the NFL after a 13-year ban on African-American players. Both players were subjected to racism from fans, players and owners, as well as brutal hits on the football field. Strode told Sports Illustrated, "Integrating the NFL was the low point of my life. There was nothing nice about it." Strode played one year of football, leaving for a long and varied acting career, including a Golden Globe nominated role as a gladiator in Spartacus and roles in John Ford Westerns. Woody from Toy Story was named in his honor. Washington retired after three years; in 1984 he was named a charter member of the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame and is featured in Wooden Hall. |

|

|

Sherrill Luke grew up in Los Angeles, attended Los Angeles High School and would sneak into the LA Coliseum to watch UCLA players Washington, Robinson and Strode play football. He was accepted to UCLA and when he didn’t make the basketball team, became yell leader instead. Popular and outgoing, he was elected UCLA’s first, and America’s second, black student body president. U.S President Harry S. Truman sent him a letter, “From one president to another.” As president he worked against discrimination on campus, including eliminating divisive language from the positions and publications of student organizations, and led the student government to reject the UC Regent’s “loyalty oath.” After graduating from UCLA with a B.A. in political science and an M.A. from UC Berkeley, he served in the United States Air Force, and subsequently received a J.D. from Golden Gate University. He went on to a long and illustrious legal career which included serving on California’s Superior Court, as chief deputy assessor for Los Angeles County and as president of the Los Angeles City Planning Commission. He also served as a member of the UCLA Foundation Board of Directors, as president of the UCLA Alumni Association and as a UC Regent. He continued to advocate for UCLA’s active role in creating a more tolerant society. Under his leadership, the Alumni Association sponsored the first-ever Conference on Diversity, increasing awareness of the many impacts of age, geographical, ethnic and gender diversity. It was the first alumni association in the United States to endorse and engage in the pivotal National Literacy Program. |

|

|

Rafer Johnson grew up in Kingsburg, California. Always an athlete and a leader, he was president of both his junior high and senior high school, where he played football, baseball and basketball. He chose to attend UCLA in part because of its commitment to diversity. He has said, “While I was touring campus, I saw pictures of the former class presidents, and one of them was a black student. I didn’t see anything like that at any other school.” At UCLA, he competed in the decathlon, breaking the world record at his fourth track meet. He also played basketball under the great Coach Wooden. He joined America's first nondiscriminatory fraternity, Pi Lambda Phi fraternity, and was elected UCLA’s second black class president. His family are all True Bruins. His wife, Betsy, graduated from UCLA, as did his daughter, Jennifer, who played volleyball, and son, Joshua, who was on the track and field team. While a student at UCLA, he competed in the 1956 Olympic decathlon in Australia, winning silver. After graduating, he won gold at the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome where he was captain of the American Olympic team, and the first African American to carry the flag in the opening ceremonies. In 1960, he turned from sports to an acting career. Inspired by a speech made by John F. Kennedy, he became friends with the Kennedy family and worked on Robert F. Kennedy’s presidential campaign. He was with RFK when he was assassinated at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles; Johnson grabbed the gun, and with the help of fellow football player Rosie Greer, apprehended Sirhan Sirhan. To honor Kennedy’s memory he joined his sister, Eunice Shriver, to help with the first Special Olympics games, enriching the lives of athletes with intellectual disabilities, and co-founded the Special Olympics Southern California. Johnson has been quoted as saying, “I wanted to give back and help others, because no one can be their best unless someone helps them.” Johnson had the honor of lighting the Olympic Flame at the 1984 Los Angeles games. He currently is a special assistant to the UCLA Athletic Director. In 2016 he received UCLA’s highest honor, the UCLA Medal, in recognition of his leadership and work supporting equality for all. |

|

|

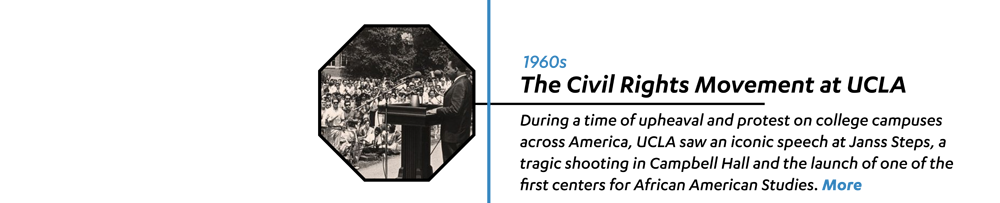

On campus, and across America, the social movements of the 1960’s were a time of upheaval and protest on college campuses. UCLA was no exception, and students on campus were involved in the civil rights movement. While UCLA was integrated, although with a relatively small number of African American students, many of them athletes, black students worked for greater representation. Students also protested Westwood businesses and apartment owners who wouldn’t sell or rent to black students. On April 27, 1965 Martin Luther King Jr. visited UCLA to deliver a speech on Janss Steps to more than 5,000 students. Recently, an audio recording of his speech was found and restored. In his speech King says, “I have faith in the future because I know somehow that, although the arc of the universe is long, it bends toward justice.” The speech came just one month after the March from Selma that led to the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Black students at UCLA, inspired by King and by the Black Panther movement’s focus on education and community improvement, advocated for greater inclusion and representation of minority students, with space on campus dedicated to them. In 1966 the Afrikan Student Union (ASU) was created to advocate for UCLA students of African descent. In 1969, 25 year-old Angela Davis, a UCLA professor, feminist and activist was dismissed by the UC Regents for being an outspoken member of the communist party. Students and faculty protested along with then Chancellor Charles Young. Young, the youngest chancellor to run a major university, defied the board, and refused to fire Davis. She was reinstated and 2,000 people attended her lecture in Royce Hall. However, eight months later, the Regents again dismissed Davis. She returned to UCLA 45 years later, in 2014 as a Distinguished Professor Emerita and Regents’ Lecturer teaching a graduate seminar in gender studies. Davis is now an author and professor at UC Santa Cruz, where she teaches courses on the history of consciousness. The Center for African American Studies was established in 1969, based on a proposal by students which stated, “Despite the obvious importance of Afro-Americans, neither the public at large nor scholars know very much about the precise role of Afro-Americans in American life, past and present.” The student center created an African American history curriculum, organized by students for students. In this time of student uprising, there were internal divisions on campus. In a dispute over leadership of the new black studies program, students were divided, some believe intentionally. On Jan. 17, 1969, UCLA students and Black Panther Party members John Huggins and Bunchy Carter, credited as a founding member of the Southern California chapter of the Black Panther Party, were slain in Campbell Hall by a member of a rival political faction. In 2010 a group of history students memorialized the classroom with a plaque. The center has been renamed the Ralph J. Bunche Center for African American Studies, and is approaching its 50th anniversary. The center resides within the UCLA Institute of American Cultures (IAC), which was established in 1972 to promote the development of ethnic studies at UCLA. The IAC brings together four ethnic studies centers on campus Bunche Center, Chicano Studies Research Center, Asian American Studies Center and American Indian Studies Center. The Bunche Center continues to pursue the goal established by the founding students to “provide a creative arena for educational development relevant to the lives and existence of Afro-Americans.” |

|

|

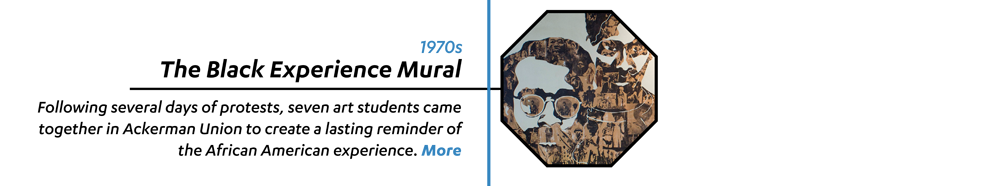

A visual icon of the black student experience at UCLA came out of a violent moment in American history. On Monday, May 4, 1970 students at Kent State College, in Ohio, were protesting the Vietnam War and the invasion of Cambodia. Four students, protesters and bystanders, were killed by members of the Ohio National Guard. These killings sparked protests and a massive student strike at colleges across the United States. At UCLA angry protesters tried to take over buildings, graffitied walls and broke windows. When students refused an order to disperse, administrators declared an illegal assembly and called in LAPD and highway patrol. A dozen students were injured and 74 were arrested. In response, Gov. Ronald Reagan shut down all California colleges and universities for four days. Students had used Ackerman as their headquarters during the unrest, and as campus returned to calm, students gathered together there. Seven black students artists came together to discuss creating something positive out of the chaos: graduate students Jane Staulz and Marion Brown, undergraduates Andrea Hill, Joanna Stewart, Helen Singleton and Neville Garrick. They submitted a proposal to paint on one of the graffitied walls with a mural of African-American history. They created a 10-foot-by-27-foot mural titled “The Black Experience.” They photocopied and enlarged an image of themselves and superimposed iconic images of black history throughout the painting. The mural was covered over by a false wall in 1992, until members of the Afrikan Student Union brought the mural to the attention of the Associated Students UCLA board of directors. It was uncovered and restored in 2014 and can be found next to Panda Express on the first floor of Ackerman Union. . |

|

|

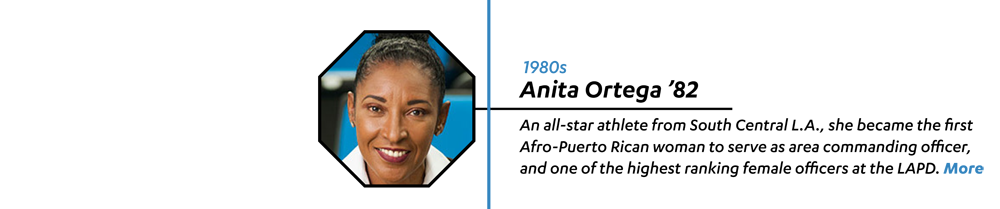

Anita Ortega grew up in South Central L.A. As a sixth grader, she asked her teacher about the letters on the bumper sticker of her car. The teacher told Ortega U-C-L-A was a college in Los Angeles and if she kept her grades high, she could go there one day. Graduating from Los Angeles High School, she was admitted to UCLA, where she earned a degree in psychology. A first-generation college student, she was a walk-on to the basketball team. She was an All-American player and the leading scorer in the 1978 UCLA national championship game against Maryland. Ortega has said about her UCLA experience, "I learned that I could be strong, confident and determined." After graduating, she joined the UCLA team as an assistant coach, and was a WNBA all-star player for the San Francisco Pioneers. Ortega joined the Los Angeles Police Department in March 1984, attaining the rank of captain at Hollenbeck Station and becoming the first Afro-Puerto Rican woman in LAPD history to serve as area commanding officer. She was one of the highest-ranking female members of the Los Angeles Police Department. Ortega also referees for NCAA basketball, something she started as a hobby, but came to love. She retired from the LAPD in the summer of 2015. She speaks to groups, especially women and young people, about overcoming challenges and dealing with obstacles. Ortiz has earned recognition in both the UCLA and LAPD Halls of Fame for her spirit, dedication and work ethic. In 2011, Captain Ortega was honored as the UCLA Latina Alumna of the Year, and in 2015 she was recognized with UCLA Award for Public Service. |

|

|

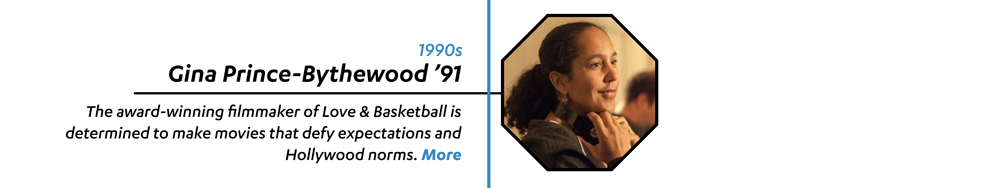

Storyteller and filmmaker, Gina Prince-Bythewood grew up in California and attended the UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television. At UCLA she joined the track team and qualified for the Pac-10 Championships in triple jump during her sophomore year. Her thesis film Stitches won the Gene Reynolds Scholarship for Directing. She also earned the Peter Stark Memorial Scholarship for Outstanding Undergraduate. After graduation she worked as a writer on the television series A Different World, and producing network television, while writing her own screenplay. Prince-Bythewood has said her goal is to break away from expectations of her as a black director, and tell universal stories. She has been quoted as saying, "For me it's just about putting people of color in every genre and making it become normal.” Her directorial debut, which she also wrote, was the widely acclaimed film Love & Basketball. Time Out London noted, “It offers an unusual perspective on female alienation and the desire for emotional attachment, while intelligent questions about gender are never far from the surface.” The film premiered at the 2000 Sundance Film Festival, and won an Independent Spirit Award for Best First Screenplay. In 2008, she wrote and directed an adaptation of the best-selling novel, The Secret Life of Bees. UCLA honored her as UCLA Filmmaker of the Year during the School of Theater, Film and Television’s annual Director’s Spotlight, a celebration of work from TFT students in 2009. In 2015, she received the Los Angeles Woman of the Year Award for her work as an artist, mentor and role model in a ceremony at the Los Angeles Music Center. Supervisor Ridley-Thomas gave her the award and said, “Her films show the goodness in people, the complexity of humanity and the ability to overcome.” |

|

|

As a public university, UCLA has a mandate to educate a diverse student body that reflects the socio-economic, ethnic, geographic and cultural backgrounds of Californians. Since the 1960s, UCLA has admitted the highest number of African American freshmen in the University of California system. In part, this was the result of outreach programs which were put in place after student protests in the late 1960s. The protests were a response to a UC study that reported that Native American, African American, Chicano, Latino and students from low-income households were not adequately prepared by their schools for UC admission. In 1998, California voted to enact Proposition 209, which eliminated affirmative action in UC admissions. This meant UCLA was required to reflect the diversity of the state's population while adhering to the restrictions imposed by Prop. 209, which required that admissions not be influenced by race, gender or ethnicity. This resulted in a drop in underrepresented minority student enrollment, including African American students. The decline went from 693 in 1995, down to 99 black first-year students in 2006, the lowest since the 1960s. Add to this the increasing competitiveness of UCLA admissions overall, academically and in the sheer number of applicants. In 2006, these findings were released to widespread concern, including the L.A. Times article, “A Startling Statistic at UCLA.” UCLA leadership declared a crisis, and was met with a groundswell of response from community leaders, UCLA supporters, alumni and students. In response, UCLA developed a number of ways to increase outreach and college preparation efforts among underrepresented groups. UCLA began what Youlonda Copeland-Morgan calls “intrusive recruiting.” The current admissions process takes into account students who show resilience in the face of hardship, and the school is finding new ways to work with community partners to combat lack of equity. Recently, UCLA’s enrollment numbers have returned to pre-Prop. 209 proportions. Last year, UCLA enrolled 279 African American freshmen, 5% of the freshman class, compared with 7% in 1995, on par with the California public high school graduation rate of 5.9% in 2015. |

|

|

In 2014 a group of undergraduate and graduate students in the Digital Humanities program were inspired to begin a project cataloging a little-know area of film history, turn-of-the-century African-American silent films. Working collaboratively, the group created the website “Early African American Film: Reconstructing the History of Silent Race Films, 1909–1930,” a searchable database of actors, crew members, writers, artists and producers. The project evolved during the #OscarsSoWhite controversy, contrasting the lack of diversity in Academy Award nominations with film’s black history from the silent movie era. These films were made for a black audience, and because the film industry was segregated, they often faced many production and funding challenges. Digital Humanities faculty member, Miriam Posner, coordinated the program and has said, “Even though so few films remain, they offer this alternative vision of African-American life in the first half of the twentieth century that’s so much more rich and complex than many things in mainstream film.” Students scoured UCLA special collections and primary-source research to build the database, including the George P. Johnson Negro Film Collection and others donated to UCLA’s Special Collections. While many of the original films have been lost, historians have found documentation of these forgotten films through journals, production notes, posters and flyers that revealed a collaborative network of African-American writers, directors, actors and producers. The database combines information from a wide range of primary and secondary sources. These movies, which have been referred to historically as part of the “race films” genre, were often documentary-style films, focused on people’s daily lives. The database includes films from 1909 to 1930 that featured African-American cast members, were produced by an independent production company and advertised as a race film in the African-American press. |

|

|