In celebration of UCLA’s first 100 years, we’re traveling back to our early days to visit some of the people, places and moments in time that have had a lasting impression on who we are as a university.

UCLA campus in 1953

The 1950s were an era of invention and development, as post-war prosperity contributed to UCLA’s expansion. Along with new buildings, new fields of study opened up drawing more students, and renowned faculty to the university. School spirit was high, and found a voice as Bruins celebrated their winning football team.

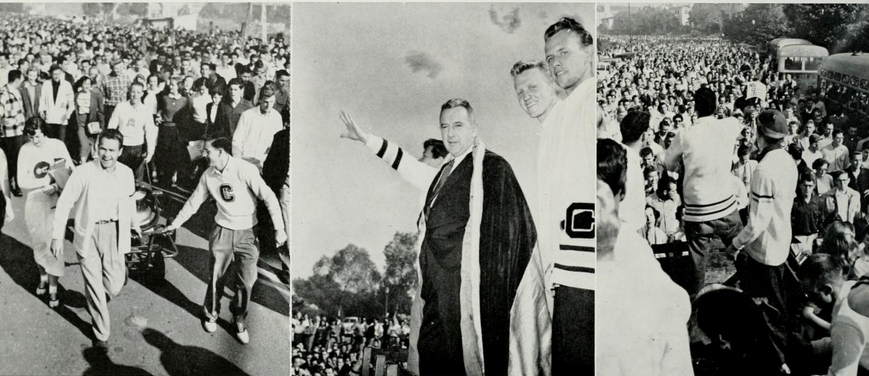

The 1950 UCLA-USC game was one for the record books. The Bruins beat the Trojans 39-0 in a decisive win and 2,000 singing students paraded the Victory Bell from the Arroyo Bridge into Westwood. Someone painted USC’s statue of Tommy Trojan blue and gold, starting a new tradition in the crosstown rivalry.

Homecoming parade floats

“Bell Rally” in celebration of the 39-0 win against USC

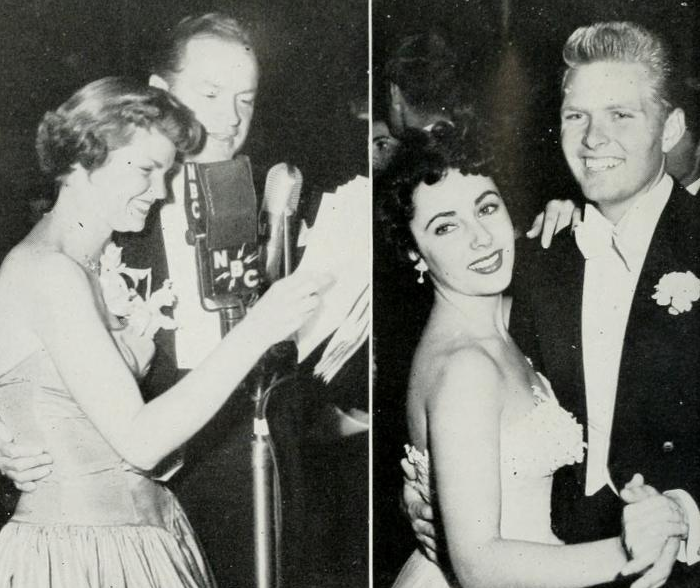

Bob Hope and Elizabeth Taylor attend UCLA’s Junior Prom.

In 1950 UCLA student Bob Precht ’51 won a contest sponsored by the Bob Hope film "The Great Lover." As winner, he escorted Eliizabeth Taylor to UCLA’s Junior Prom. Although he attended the dance with the movie star, he met his future wife, UCLA student Betty Sullivan Precht ’52, daughter of television host Ed Sullivan, at the event. The dance was held on a Paramount Studios sound stage, and Bob Hope happened to stop by to dance with Prom Queen Joyce Felson ’51.

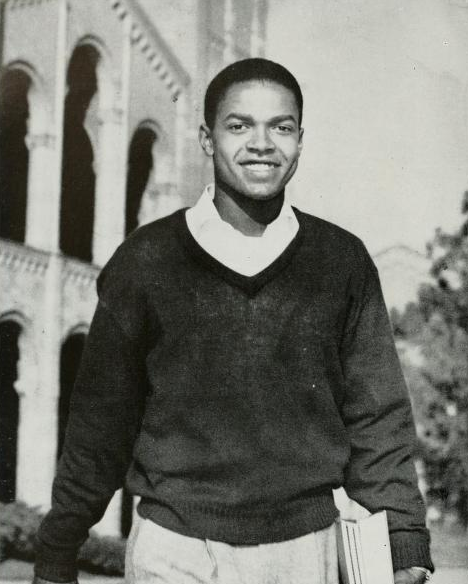

Sherrill Luke ’50, UCLA’s first black student body president.

As campus bustled with creativity, author Ray Bradbury needed a quiet place to write. While the author was not a UCLA student, he discovered a room in the basement of Powell Library with typewriters for rent. It was here Bradbury created the literary masterpiece “Fahrenheit 451,” spending $9.80 to finish his story about a dystopian world where firefighters burn books. The classic includes quotes from books he found in the Powell stacks — there were nearly one million volumes in 1950. In 2002, Bradbury wrote in UCLA Magazine, “Since I'm a library person, having educated myself in the libraries of Los Angeles, all of this concerned me, and the older I got the more I wanted to write stories about libraries and books.”

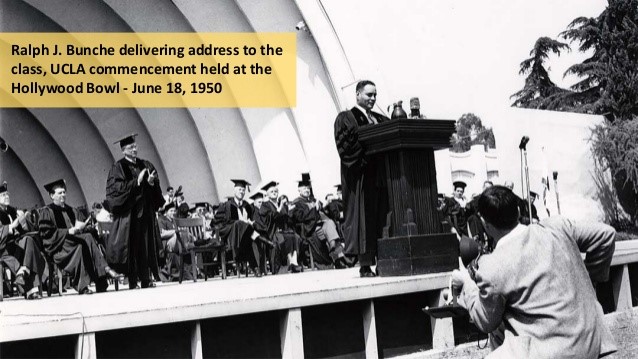

Ralph Bunche ’27 speaking at the 1950 graduation at the Hollywood Bowl.

In 1947, Bunche traveled to the Middle East to help mediate between newly founded Israel and its Arab neighbors. While there, war erupted and Bunche began peace negotiations between the nations, resulting in the signing of the 1949 Armistice Agreement. On his return, New York City threw him a ticker tape parade. Bunche received the Nobel Prize for Peace for this work. He continued to serve at the UN and actively support the Civil Rights Movement. Bunche received an honorary degree from UCLA in 1950 and was the featured speaker at graduation, held at the Hollywood Bowl.

.jpeg) In 1952, UCLA began a unique program known as Project India, with specially selected groups of students traveling to India to share American culture, in part in an attempt to stop the spread of communism. One UCLA student, Sister Diane Donoghue ’54, was so affected by the extreme poverty she saw there it influenced her life’s path. An active student leader at UCLA, where she was involved with University Religious Conference projects, including UniCamp and the Panel of Americans, upon graduation she chose to enter the Sisters of Social Service, a Catholic order devoted to serving the poor.

In 1952, UCLA began a unique program known as Project India, with specially selected groups of students traveling to India to share American culture, in part in an attempt to stop the spread of communism. One UCLA student, Sister Diane Donoghue ’54, was so affected by the extreme poverty she saw there it influenced her life’s path. An active student leader at UCLA, where she was involved with University Religious Conference projects, including UniCamp and the Panel of Americans, upon graduation she chose to enter the Sisters of Social Service, a Catholic order devoted to serving the poor.

Clarence A. Dykstra, provost and vice president, passed away in 1950. A beloved figure on campus, he is credited with revitalizing UCLA and setting it on course to become the world-renowned institution of today. After an 18-month search and consideration of more than 50 candidates, the Regents announced the appointment of Raymond B. Allen. Allen was chosen in part for his experience with medical programs, since UCLA was developing its Medical Center and schools of medicine, dentistry and nursing, as well as his anti-Communist reputation.

Clarence A. Dykstra, provost and vice president, passed away in 1950. A beloved figure on campus, he is credited with revitalizing UCLA and setting it on course to become the world-renowned institution of today. After an 18-month search and consideration of more than 50 candidates, the Regents announced the appointment of Raymond B. Allen. Allen was chosen in part for his experience with medical programs, since UCLA was developing its Medical Center and schools of medicine, dentistry and nursing, as well as his anti-Communist reputation.

The social sciences building was renamed Bunche Hall in 1969, the only teaching building on campus named after a graduate. At the dedication, Bunche said, “UCLA is where it all began for me, where in a sense I began. College for me was the genesis and the catalyst. Peace, like war, can usually be won only by bold and courageous initiatives and by taking some deliberate, calculated risks.”

.jpeg)

Sister Diane Donoghue ’54, founder of Esperanza Community Housing in South Los Angeles.

Sister Donoghue devoted her life to empowering the underrepresented. She became the community organizer for a South Central Los Angeles parish in 1985, working tirelessly assisting families in creating safe, affordable housing. Her work led to the creation of Villa Esperanza Apartments, and 10 similar developments, with affordable housing units for large families, a community center and on-site Head Start. Donoghue set a shining example of the true meaning of community service and received the 2007 Edward A. Dickson Alumnus of the Year Award.

Clarence Dykstra, former provost and vice president.

In 1951 the Board of Regents granted UCLA further independence from UC Berkeley. The reorganization plan gave UCLA autonomy, calling for a chancellor instead of provost, a title that included both academic and administrative authority. Allen would be the first to hold the title of Chancellor of UCLA on Dec. 14, 1951.

In the 50s, the building boom continued across campus, funded in part by wartime taxes granted to UCLA by the California State Legislature. In 1947, the UC Regents had chosen Welton Becket, designer of iconic buildings such as the Cinerama Dome, Dorothy Chandler Pavilion and Capitol Records among many others, as the master architect to supervise the campus expansion and modernization. Becket blended the original Romanesque buildings with efficient steel and brick structures. Becket’s firm created a long-range master plan, an idea he called “total design,” including buildings, landscaping, parking and a campus road. It was during this time the arroyo was filled, creating 24 additional acres for building.

Left: Graduating Class of 1955 - Right: Mary Nydorf, Class of 1957

UCLA Medical Center in 1955

The hospital had 12 miles of corridors, with beds for 320 patients and space for another 500 to receive outpatient treatment. The building was designed with wings that could be added on to later. In 1955 the hospital admitted its first patients, Frederic Stoetzel was the first to have surgery at the new facility. In 1956 the UCLA Medical Center was the first hospital in the Western United States to perform open heart surgery. Although it is one of the youngest academic medical centers in the country, the UCLA Medical Center is now one of the great medical centers in the world. A state-of-the-art academic facility, it is the designated hospital for a sitting U.S. president who becomes ill or injured west of the Mississippi.

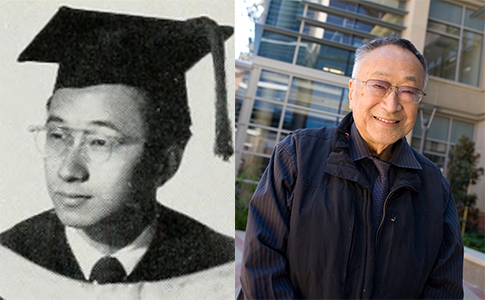

Paul Terasaki in 1950 and 2011. He developed a procedure to assess the compatibility of organ donors and recipients, saving thousands of lives.

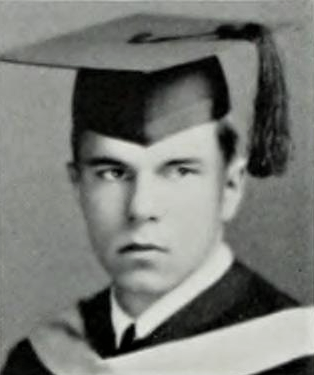

Glenn Seaborg ’33, winner of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

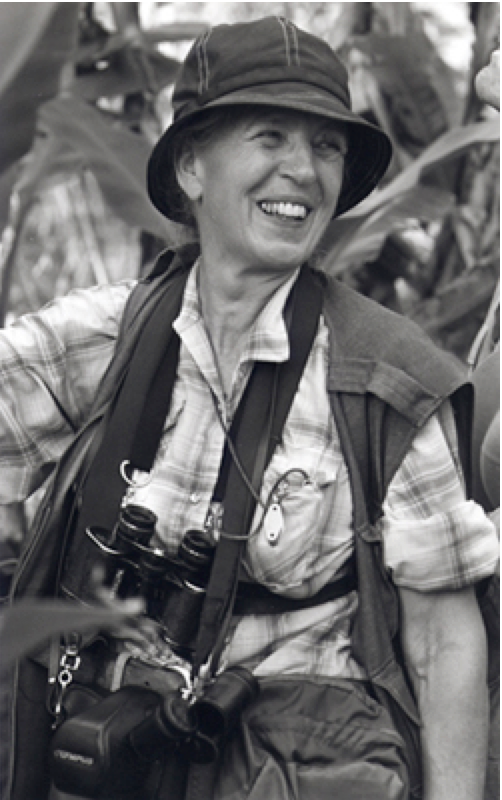

In 1956, Mildred Mathias was appointed director of UCLA’s Botanical Garden. She came to UCLA in 1947 as an herbarium botanist, became a lecturer in 1951 and an assistant professor four years later. Mathias had earned her Ph.D. in 1929, focusing her studies on Umbelliferae, or carrots, discovering over 100 types, with a Mexican umbelliferae, Mathiasella, named in her honor. An expert on plant taxonomy, ethnopharmacology and ecotourism, she made expeditions to herbalists and healers in Peru, Ecuador, Chile, Costa Rica and Zanzibar. Later, she led UCLA Extension groups around the world to learn about preserving nature.

Mildred Mathias - professor, botanist and director of the UCLA Botanical Garden.

In November 1959, UCLA’s first residence hall on the Hill opened, named for popular former provost Clarence Dykstra. Dykstra was a proponent of creating on-campus housing as a way to foster students’ cultural and intellectual lives and campaigned to overturn a UC policy preventing on campus student housing. Dykstra died in 1950, but students carried on his vision, getting regental approval for UCLA’s first dorm. Dykstra Hall housed 800 men in a 10-story building. Within a few years the top three floors of Dykstra Hall were opened to women, making it the first coed dorm in the nation.

Dykstra, UCLA’s first residence hall on the Hill.

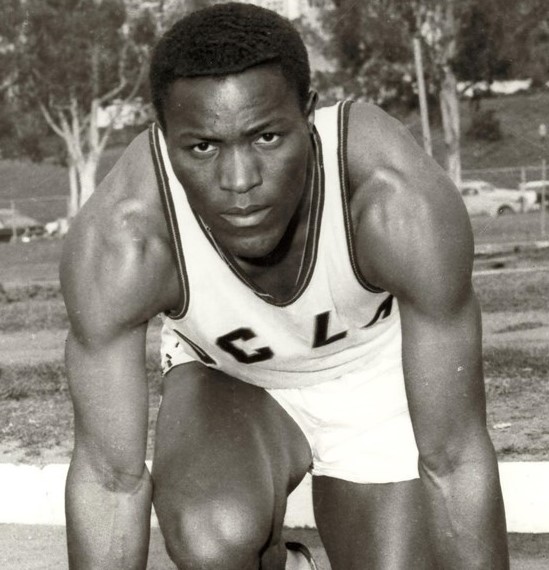

Olympic gold medalist, Rafer Johnson ’59, served as student body president and later co-founded the California Special Olympics.

Johnson retired from athletics to begin a career as a commentator, political activist and philanthropist. He found his passion in giving back, serving as an original member of the Special Olympics Board of Directors, and was instrumental in creating the California Special Olympics. In 1984, Johnson lit the Olympic torch at the Los Angeles Olympics, and in 2016, he was awarded the UCLA Medal, presented to those whose work embody UCLA’s highest ideals.

In 1958 UC regents changed the school’s official name to “University of California, Los Angeles” and in 1959 the Progress Fund launched UCLA’s first major fundraising campaign. Alumni raised more than $2.2 million for scholarships and other university programs. The Alumni Association also played an active role in the search for a new chancellor, leading to the selection of Dr. Franklin Murphy, a doctor and professor of medical history, who worked to build UCLA’s reputation worldwide. It was Murphy who asked campus telephone operators to greet callers using UCLA instead of University of California. Prior to 1958, the university was called the University of California at Los Angeles. The Regents dropped the "at" and the campus became officially known as University of California, Los Angeles, or UCLA for short.

The 1950s had truly been a decade of Bruin spirit, invention and growth at UCLA — winning sports teams including a football national championship and the university’s first NCAA championship, two Nobel Laureates, a state-of-the-art hospital, the university’s first chancellor and an influx of talented faculty and students. The 1960’s Southern Campus yearbook told that year’s graduates, “You were spectator to an era where traditions of the past merged with desires for the future. Where the entire University of California was rapidly expanding, so was UCLA, with new buildings, broader curricula, and more students. You were part of a farsighted year.”

Dr. Murphy would lead UCLA through the turbulence of the 1960s, a decade that would bring more growth to campus, and would be shaped by events including the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights and Free Speech Movements.

Series Archive