Black Bruin History at UCLA

In celebration of Black History Month, we are celebrating UCLA’s Black Bruins. For 100 years, they have been among the best and the brightest — activists, leaders, teachers, role models and trendsetters. They are politicians and athletes, artists and diplomats, doctors, lawyers and everything in between. There have been sit-ins, setbacks, protests and walk-outs, and the reward has been progress. They walk in the footsteps of those who came before them, and blaze a path for those that follow, in search of a more just and equitable world.

A NEW UNIVERSITY

UCLA was established in 1919, at a time when Black Americans were moving to Los Angeles to escape the violence and bigotry of the South, the beginning of the Great Migration. UCLA was not segregated, yet was not immune from the systemic racism of the time. Only a small number of Black, and other minority students were enrolled in what was then the Southern Branch of the University of California on Vermont Avenue.

Downtown’s Central Avenue was the heart of Los Angeles’s Black community. Discriminatory racial covenants kept people of color from living in many neighborhoods, including near campus. Black students were not afforded accommodations, were denied the use of university facilities and most had to work full-time to pay tuition. Those who were able to overcome the obstacles and enroll — often by attending schools with a college preparatory focus, by having mentors or friends who helped navigate the process or by winning an athletic scholarship — were restricted from fully participating in campus and academic life.

For a glimpse of Black life at the turn of the century, visit the “Early African American Film: Reconstructing the History of Silent Race Films, 1909–1930” database. It is the work of a group of students in the Digital Humanities program who began cataloging turn-of-the-century African-American films in 2014.

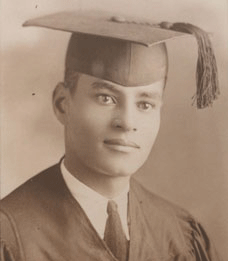

Dr. Ralph Bunche '27

Black students were not invited to join most collegiate activities, including UCLA’s fraternities and sororities, so they established their own. UCLA’s first Black sorority, Delta Sigma Theta, and fraternity, Kappa Alpha Psi, were chartered in 1923. They were a haven for students, fostering community and support. Their members have had a profound impact on Los Angeles. Miriam Matthews (1922–1924), was the first president of Delta Sigma Theta and would become a civil rights activist, historian, preservationist and Los Angeles’ first Black librarian.

BREAKING BARRIERS

In 1929, UCLA students started the school year at the new Westwood campus, a beautiful site that was significantly further from Central Ave. The hardships of the Great Depression inspired political activism and the movement to create structural change in Black American life. These years would lay the groundwork for the Civil Rights Movement.

Augustus Freeman Hawkins ’31 entered politics to champion worker’s rights. He said, “I had struggled to go to college, only to find out that I had no better opportunity than one who hadn't gone to school at all.” He became the first African American from California elected to Congress and a founding member of the Congressional Black Caucus.

Bunche and Matthews broke barriers as the first in their fields, paving the way for many more historic “firsts,” including: Yvonne Braithwaite Burke ’53, the first Black woman to represent the West Coast in Congress, and the first woman to give birth while serving in Congress; Michelle King ’84, the first Black woman superintendent of the Los Angeles Unified School District, who graduated with a bachelor's degree in biology and said UCLA was where she “found her voice;” and Kim Hamilton-Anthony ’90, the first African American gymnast to receive a full athletic scholarship.

Most major college athletics programs did not allow Black players until 1947. In 1939, very few college football teams had even one Black player on their roster. The Bruins had four — Jackie Robinson (1939-1941), Kenny Washington ’41, Woody Strode ’39 and Ray Bartlett ’44 — and they led UCLA football to its first undefeated season.

Woody Strode '39, Jackie Robinson, Kenny Washington '41.jpg)

(From left) Woody Strode '39, Jackie Robinson, Kenny Washington '41

Washington and Strode were two of college football’s best, yet the NFL refused to sign them. Local Black newspapers reminded the Rams that by playing at the L.A. Coliseum, supported by public funds, they were bound by law to be integrated. In 1946, Washington and Strode re-integrated the NFL, where they were subjected to racism from fans, fellow players and owners. Strode told Sports Illustrated, "Integrating the NFL was the low point of my life. There was nothing nice about it."

UCLA‘s first Black football player James C. Williamson played for the Bruins in 1919. The James C. Williamson Award was established in 2016 and presented each year on MLK Remembrance Day.

These trailblazing athletes faced challenges both on and off the field. They were the first in a tradition of Bruin athletes, including Arthur Ashe ’66 and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar ’69, who have been champions for civil rights, and who were strongly criticized at the time for their activism. By using their fame as a tool to create change, they were the forerunners of today’s activist athletes.

Bruin excellence inspired others to follow, and their stories can be found throughout UCLA history. Jackie Joyner-Kersee ’86, the most decorated woman in track and field history, has said her hero Evelyn Ashford (1976-78) gave her the confidence to run track, “It was incredible to see someone who looked similar to me.”

Tom Bradley ’41, the first, and only, Black mayor of Los Angeles and the second Black mayor of any major U.S. city, was encouraged to attend UCLA by distinguished scholar and track champion James Lu Valle ’36, M.S. ’37. He later thanked LuValle, saying “[He] made it possible for me to come here and that changed my life.” Bradley had been told by a middle school counselor, “You’re doomed to be denied that opportunity to go to college. Take some studies

that are going to lead to manual labor because that’s about as much as you’re going to be able to hope for.” Bradley would be elected to an unprecedented five terms as mayor.

Retired Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Sherrill Luke ’50 recalled sneaking into the L.A. Coliseum to watch UCLA football games. He was elected UCLA’s first, and America’s second, Black student body president. Luke’s story encouraged athlete, actor and public servant Rafer Johnson ’59 to choose UCLA saying, “It’s not just because of UCLA’s long history with athletes of color, like Jackie Robinson and Woody Strode. While I was touring campus, I saw pictures of the former class presidents, and one of them was a Black student. I didn’t see anything like that at any other school.”

As America entered World War II, job opportunities drew Black Americans to Los Angeles. The city's white power structure responded by intensifying racial discrimination. While the Supreme Court overturned racial housing covenants in 1948, Rep. Diane Watson ’56 recalled that in Westwood Village in the 50s, “You could not live on Hilgard if you were Black, except at the YMCA.”

In a move towards greater equity, the 1954 landmark Supreme Court decision, Brown v. Board of Education, ended racial segregation in public schools, yet years of redlining meant many schools remained segregated. At UCLA, students began advocating for a more progressive and inclusive curriculum. The UCLA African Studies Center established in 1959, was a distinguished research, teaching, and outreach center, among the first of its kind on any college campus.

FIGHT FOR CIVIL RIGHTS

Change swept across America in the 1960s, driven by the Civil Rights and Black Power movements. Claudia Mitchell-Kernan, former vice chancellor of the graduate division, said, “[Student activism] led future generations to achieve a greater sense of empowerment on campus and in the world.” As progress moved across America, the UCLA community began to build a more just campus where all students could thrive.

In a powerful act of nonviolent protest, the Freedom Riders challenged segregation in the South. In 1947, the Supreme Court had ruled, in Morgan vs. Virginia, that segregation in interstate travel was prohibited, yet it persisted in parts of America. Activists Helen Singleton ’74 and Dr. Robert Singleton ’60, M.A. ’62, Ph.D. ’83, president of the UCLA chapter of the NAACP, travelled to Mississippi to ride segregated busses, where they were arrested and incarcerated. Singleton said, “What I wanted was to be as much of an instigator as I could and keep things happening, because I knew it was all bigger than me.” Other UCLA Freedom Riders included: Carroll Gary Barber, Albert Barouh, Marilyn Eisenberg, Winston Fuller ’60, Joseph Gerbac ’62, J.D. ’65, Michael Grubbs, Alan Kaufman, William Leons, Steven McNichols, Rabbi Philip Posner ’62, Max Pavesic ’61, Sam Townsend ’61, Mike Wolfson ’66 and Robert Farrell ’61. Farrell was arrested while sitting in a segregated coffee shop. He later served four terms as an L.A. City Councilman.

In the 1960s, student groups including NAACP and CORE, created social change in Westwood Village. They first worked to integrate Westwood barbershops, which refused to cut Black men’s hair. When they refused, Chancellor Murphy opened a barbershop in the basement of Kerckhoff. Students then began to approach Westwood apartment owners. Those who would not rent to Black students were removed from campus listings. While the administration supported the activists, change came slowly. In the fall of 1968, when Carolyn Webb '69, M.A. '72, was elected UCLA's first African American homecoming queen, some Westwood businesses refused to honor a longstanding tradition to present her with gifts, as they had to past winners.

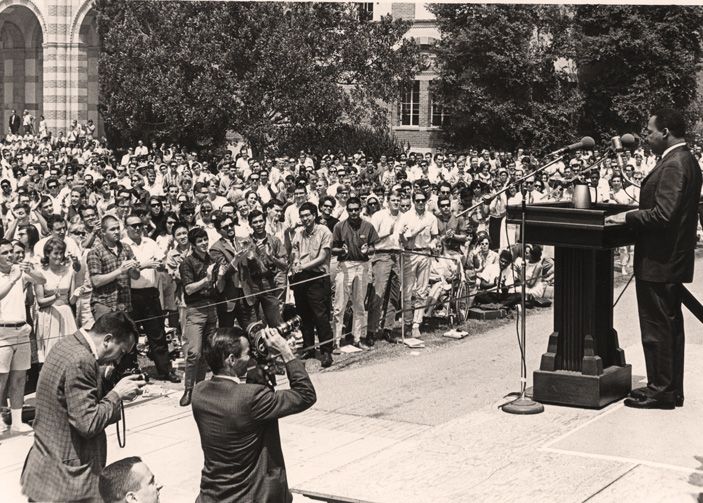

Martin Luther King Jr. on Janss Steps

At UCLA, Dr. King announced the Summer Community Organization and Political Education (SCOPE) voter registration project. Twenty UCLA students joined that summer. Years later, Coretta Scott King enlisted Clayborne Carson ’67, M.A., ’70, Ph.D. ’75, as director of the King Papers Project. Speaking at UCLA, Carson said, “If [King] were still here he would be the one asking us if all our struggles today really give purpose to our lives.” Dr. King spoke of ending segregation, yet California passed Prop. 14 later that year, nullifying the Rumford Fair Housing Act which had ended racial discrimination by landlords. This act is considered by some to have been a cause of the 1965 Watts Rebellion.

By 1965, the landmark Voting Rights Act, 24th Amendment banning poll taxes and the Civil Rights Act had all passed, in a move to protect the rights of all Americans.

As the news of Dr. King’s assassination reached UCLA in April 1968, thousands of students marched through Westwood Village. Members of the Black Student Union instead chose to march to Ackerman, where they burned American flags and left campus. Sophomore Aaron Riviers (1967-68) was quoted as saying, "We are deeply saddened and shocked upon learning of the death of Dr. Martin Luther King. It is indeed a symbol of racial prejudice, bigotry and racism in white America.” Virgil Roberts ’68, M.A. ’69, head of the Black Student Union (BSU) education committee said, "We are going home to be with our people.”

The Harambee Council is the governing body of the Afrikan Student Union. ASU functions as the “umbrella” organization for more than 40 Black student organizations that contribute to the Black student, staff and faculty populations, be they professional, cultural, political or social.

The turmoil brought about change, as students worked to build a more just campus that respected diverse voices. Campus’ first Black student organization was the Black Student Union, founded in 1966. Chairperson J. Daniel Johnson ’69 said, “UCLA was the place to come if you were a young, African American male and you wanted to achieve in society. We just felt that we could overcome anything, we could accomplish anything, just give us the opportunity.” The name was later changed to the Black Student Alliance to reflect the connection to other Black organizations and African and Caribbean students on campus, and finally to the Afrikan Student Union (ASU) in solidarity with Africa and Black people across the diaspora.

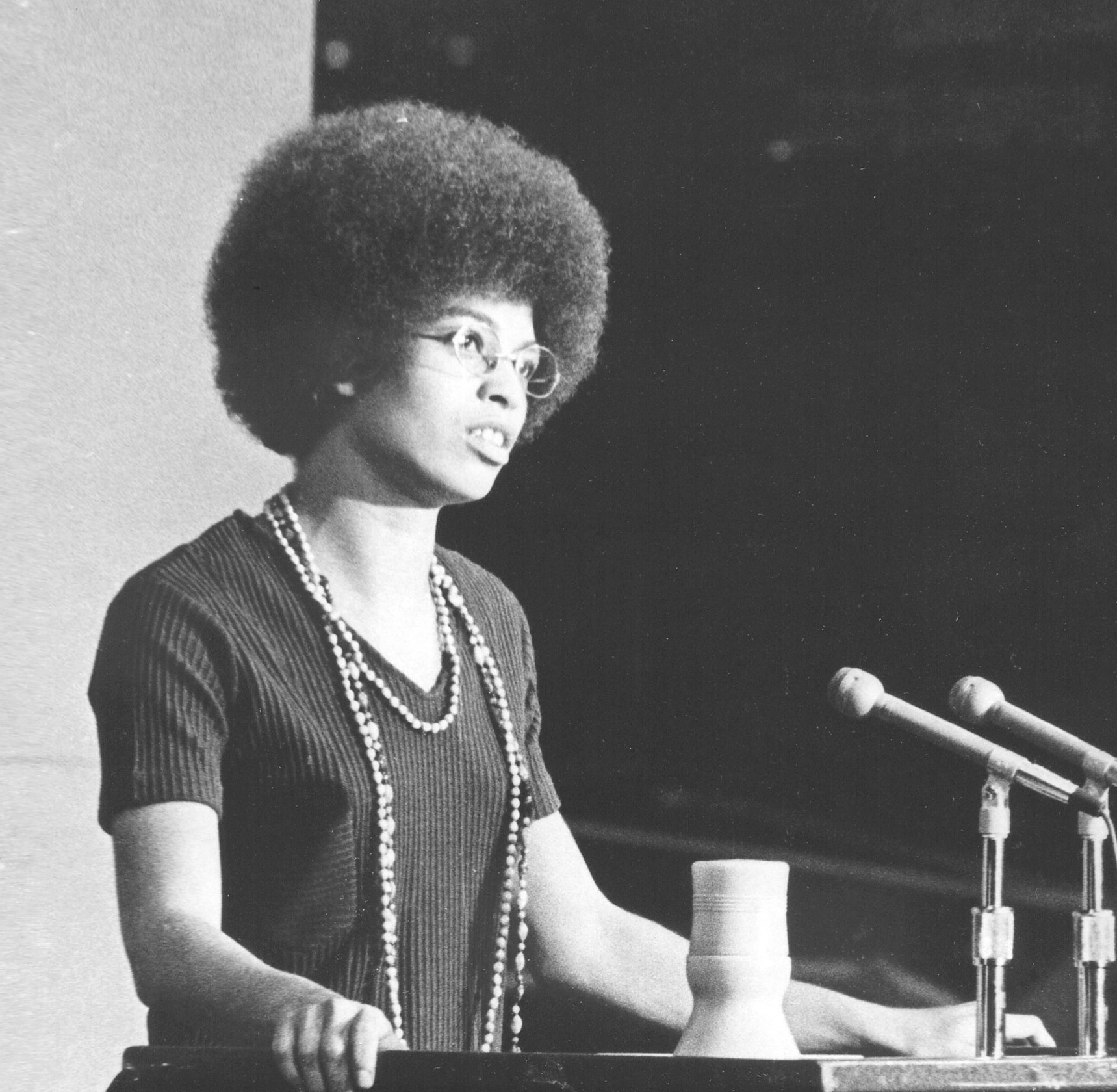

Angela Davis

Chancellor Young also hired Dr. C.Z. Wilson in 1971 as the first Black UCLA vice chancellor. At the time, Wilson was the top-ranking African American in the entire University of California system. One of the most influential Black administrators in UCLA history, he was instrumental in bringing Affirmative Action to UCLA.

Influential Black alumni, including Mayor Bradley ’41, Larry Hollyfield ’73, Herschel Ramsey ’80 and triple Bruin and UCLA Vice Chancellor emeritus Winston Doby ’63, M.A. ’72, Ed.D. ’74 initiated the UCLA Black Alumni Association (UBAA) in 1968. Today, UBAA fosters connections and supports Black graduates of UCLA. They have raised more than $3.4 million dollars in scholarship support and received the UCLA Alumni Network of the Year Award in 2018.

Tragedy struck campus when two members of UCLA’s Black Panther Party, students Alprentice “Bunchy” Carter and John Jerome Huggins Jr., were shot and killed in Campbell Hall — in an alleged internal dispute. Elaine Brown ’68, who would go on to lead the Panthers, said the men “talked about uniting the community and the campus.” Carter and Huggins were among the first group of students admitted under the High Potential Program (HPP), an effort to widen access for students from underrepresented backgrounds. In 1971, HPP was combined with the Educational Opportunity Program to create what is now the Academic Advancement Program, a collection of innovative programs serving students from multi-ethnic, low-income, first generation and multiracial backgrounds.

Black students at UCLA advocated to have their culture studied at the university. As a result, the Ralph J. Bunche Center for African American Studies was established in 1969 to develop African American Studies at UCLA, one of the first centers of its kind. The establishment of UCLA’s prestigious Institute of American Cultures (IAC) and its four ethnic studies centers — American Indian, African American, Chicano and Asian American — was a step forward by the University. The IAC continues to advocate for academic freedom, civil and human rights and community activism.

In the midst of these heightened tensions, a group of Black students were admitted to the UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television’s Ethno-Communications program. Influenced by politics and the mainstream portrayal of African Americans in film, they developed a collaborative new style called the "L.A. Rebellion," an expression of Black pride and dignity by these early Black filmmakers. Julie Dash ’74 became the first Black woman to have her film (“Daughters of the Dust”) receive general theatrical release in the United States.

A major flashpoint of the era sparked student-led strikes across the country when, in 1970, at a protest at Kent State against the Vietnam War, the Ohio National Guard shot and killed four people. At UCLA, more than 1,000 students gathered for a rally that turned violent. Administrators called in the LAPD and declared an illegal assembly. As campus returned to calm, seven Black students came together to create something positive. Their mural, “The Black Experience,” includes photos of the artists alongside images of African American history.

"A World Class University"

The 1980s and 90s saw the proliferation of the Internet, the magnitude 6.7 Northridge earthquake and the Los Angeles Olympics, where Bruin athletes won 37 medals. Students protested the injustice of South African apartheid, the passing of the anti-affirmative action Prop. 209 and the anti-immigration Prop. 187. Los Angeles erupted for five days of civil unrest following the acquittal of the LAPD officers who stopped and beat Rodney King. UCLA also saw two more significant firsts. Cynthia McClain Hill ’78, J.D. ’81, became UCLA’s first Black woman student body president in 1976. A first-gen student, in 2020 McClain Hill was elected president of the Los Angeles Board of Water and Power Commissioners. And in 1983, Kimberly Cohn became the first Black editor of the Daily Bruin.

Black students have been leaders in moving the campus forward on important issues. Dion Raymond ’86 chose to attend UCLA because, “If you wanted to be socially, politically active, UCLA was really the best place to learn inside the classroom and outside the classroom.” Raymond, currently president of the UCLA Black Staff & Faculty Association, was active in organizing anti-apartheid protests at UCLA as the BSA chairperson. The student group the Third World Coalition (TWC), led by John Caldwell ’81, advocated for corporate divestment from South Africa. The TWC organized BIPOC students to lead student government, where they successfully advocated for divestment and student-run retention and access programs. Tim Ngubeni ’79, M.A. ’80, M.P.H. ’82, was a leader in the divestment campaign, the founder and first fulltime director of the Community Programs Office (CPO), and a mentor for years to many UCLA student activists.

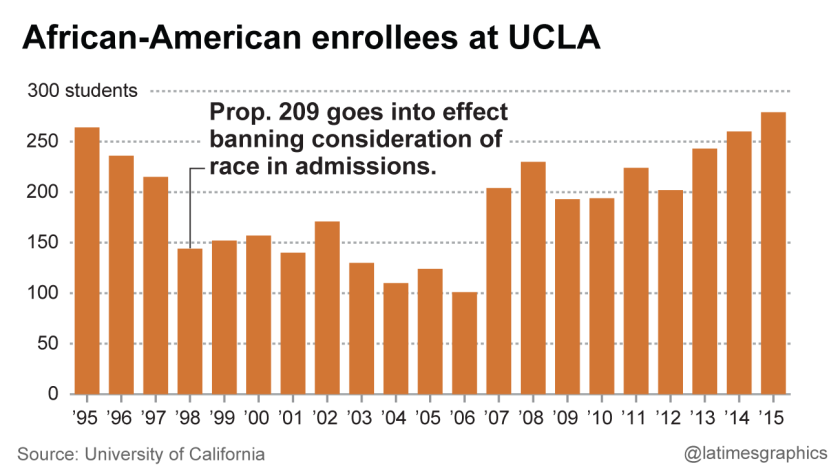

African American enrollment declines at UCLA since Prop 209.

To encourage an understanding of a diversity of experiences, a majority of UCLA students voted to pass the Communicating Unity Through Education Initiative in 2011. In 2015, UCLA established a diversity requirement. Students now are required to take a course that "addresses racial, ethnic, gender, socioeconomic, sexual orientation, religious or other types of diversity."

To increase the number of competitive Black students, UCLA began what Vice Provost, Enrollment Management, Youlonda Copeland-Morgan has called “intrusive recruiting.” Several student groups also began working with communities of color facing access and retention issues. These included S.H.A.P.E. (Students Heightening Academic Performance through Education) to mentor inner-city high school students and the Academic Supports Program (ASP), a student-led retention project of ASU.

BLACK LIVES MATTER

Patrisse Cullors '12, Co-Founder of Black Lives Matter

UCLA professors have also played a role in creating increased equity and access in education. The Black Male Institute (BMI) was founded by Tyrone Howard, associate dean for Equity & Inclusion at UCLA Graduate School of Education & Information Systems. He says, “If we allow these young men to define themselves and their successes in their language, with their words and stories and experiences, then perhaps that becomes a small part of the process of redefining the narrative.” Professor Mark Sawyer, a champion for access and diversity, played a primary role in the creation of UCLA’s Department of African American Studies and to move beyond the traditional view of race in politics he co-founded the Race, Ethnicity, and Politics Program in the UCLA Department of Political Science.

Darnell Hunt, dean of the UCLA College Division of Social Sciences, is the lead author of the Bunche Center’s Hollywood Diversity Report. First published in 2014, it is an annual series that examines the relationship between diversity and profit in the entertainment industry. The report has consistently found people of color remained underrepresented in the film and television industry.

Black student voices went viral in the spoken word video “The Black Bruins,” featuring Sy Stokes ’15 and members of the Black Male Institute. “The wounds of our past have healed. We are not asking for a handout. We are asking for a level playing field.” In the fall of 2015, following the fraternity and sorority "Kanye Western'' party, ASU members protested students leaving the party, some in blackface, according to the Daily Bruin. Photos of students in blackface had been published in the yearbook as late as 1985. Dr. Chad Williams ’98, former chair of ASU said, “The statement #BlackBruinsMatter certainly speaks to the present, but it must also speak to the past as well. Especially if we want to understand the reasons why the current racial demographics and attendant climate is so problematic and creates the conditions for incidents like the frat party.”

Sherrilyn Ifill, a leading civil rights lawyer, spoke at UCLA’s Thurgood Marshall Lecture Series in 2020. She told the audience, “This is a movement time. And that movement of young people is powerful. They push us to do things faster.” The Bunche Center inaugurated the Thurgood Marshall Lecture Series on Law and Human Rights in 1986, to pay tribute to the first Black Supreme Court Justice, Thurgood Marshall.

The Black Lives Matter movement gained urgency in 2020. Chanting the names of Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, UCLA students, faculty, staff and community members marched to protest racial injustice and police brutality. UCLA students advocated for a campus environment that protects Black students and fosters their academic success. They demanded all UC campuses divest from the UCPD, opposed the use of Jackie Robinson Stadium to confine arrested protesters and repeated the need for a fully funded Black Resource Center at UCLA.

There has also been a call to recognize the Black student experience through the lens of the larger issues facing the Black community. One such issue is the COVID-19 pandemic, which has exposed inequities among people of color. UCLA is working to improve health care access and treatment for underrepresented minority groups. Linda Burnes Bolton, M.S.N. ’72, M.P.H. ’76, DR.P.H. ’88, has dedicated her life’s work to increasing cultural diversity in healthcare. She has said, "The nursing profession plays a critical role in achieving our country's vision of an effective, affordable health care system that is accessible and responsive to all.” Dr. Vickie M. Mays leads the UCLA Center on Minority Health Disparities. Regarding the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Mays has said, “We are all connected. The extent to which we allow members of our society to be unequal is the extent to which we endanger the health of all.”

In 1956, UCLA hired Betty Smith Williams, to teach public health nursing. She was the first Black person hired to teach at the university level in California.

Responding to the protests and student demands of 2020, UCLA has introduced an initiative to build a more inclusive campus. Chancellor Gene Block and Executive Vice Chancellor and Provost Emily Carter said, “UCLA must be a place that respects and empowers all Bruins and that works to overcome anti-Blackness and other manifestations of racism throughout society.” Plans include the Black student resource center, new faculty positions, fellowships, fundraising and research support. Chancellor Block promised to continue, “Our work to fight racism will not end with these steps. More changes will be coming to challenge the structural racism that exists in our education system, from kindergarten through graduate school, including at institutions like UCLA.”

In 2020, the Black Student-Athlete Alliance announced their organization, saying, “Through this group, we want to create a safe space for Black athletes to grow & elicit change on campus and beyond. We will no longer remain silent.” The alliance was founded under the leadership of student-athletes, including women’s basketball senior forwards Lauryn Miller and Michaela Onyenwere.

The story of Black students at UCLA continues. It tells of the struggles and the successes, for individuals, famous and ordinary, and as a record of the larger UCLA community. Dr. Jonli Tunstall ’05, Ph.D. ’11, has said, "It's about creating a ripple effect and so by investing in one student or a group of students, those students will then go on to invest in other students."

Viral sensation Nia Dennis performs floor routine celebrating Black Excellence

Despite a century of great progress, underrepresented students continue to face challenges — including lower retention rates, difficulty adjusting to college life and financial setbacks. In an L.A. Times op-ed, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar said, “Racism in America is like dust in the air. It seems invisible — even if you’re choking on it — until you let the sun in. Then you see it’s everywhere. As long as we keep shining that light, we have a chance of cleaning it wherever it lands. But we have to stay vigilant, because it’s always still in the air.” He continued, “So you know, we got a lot of work to do. And all of us have to be involved in it, every American."

Previous stories on Black Bruin History: