Imagine if every organized event you attended — some of which begins with the National Anthem, the Pledge of Allegiance, maybe even a prayer — also included an acknowledgement of the Indigenous peoples who historically inhabited that land upon which the event was taking place?

The message was co-signed by Dr. Mishuana R. Goeman, associate professor of gender studies and chair of the American Indian Studies Interdepartmental Program, as well as Special Advisor to the Chancellor on Native American and Indigenous Affairs. Goeman crafted the message with Tongva leaders through an iterative process that began before she became chair of the department in 2017.

The message was co-signed by Dr. Mishuana R. Goeman, associate professor of gender studies and chair of the American Indian Studies Interdepartmental Program, as well as Special Advisor to the Chancellor on Native American and Indigenous Affairs. Goeman crafted the message with Tongva leaders through an iterative process that began before she became chair of the department in 2017.

At last year’s Spring Sing, the first event of UCLA’s Centennial Celebration, the first words heard by the thousands in attendance were, “UCLA, like all campuses in the UC system, is a land-grant institution. This means that it resides on land provided by the state that was historically the homeland of Indigenous peoples. Tonight, let us pay our respects and acknowledge the Gabrielino-Tongva peoples as traditional caretakers of this land. Because it is on this land that we are so lucky to work, teach and learn as a community.”

A message sent by Chancellor Block to the campus community in August of this year explained the purpose of this acknowledgement. “It is important that UCLA prioritize respect for both the historic culture and the contemporary presence of American Indians throughout California, and especially in the Los Angeles area.

“To that end, and particularly as a public and land-grant institution, it is important for UCLA to acknowledge that our campus resides on what was historically the homeland of Indigenous peoples who were dispossessed of their land…

“We encourage all UCLA schools, departments, institutes, units and other campus entities to include a similar acknowledgement at any significant public events that you host on campus property.”

Dr. Mishuana Goeman

This acknowledgement, according to Goeman, serves as an introduction to the Tongva people; a first step in educating the world about the mistreatment and, in many cases, horrors visited upon native peoples. It’s an examination of what is being done today, and what is necessary for the Tongva people to begin to assume their rightful place in the past, present and future of this region.

When people write about Tongva people or any Indian people: it’s all about the past; it’s not about the present and a living culture, living communities or any of that.

The names Gabrielino and Tongva may be unknown to many - and as unfamiliar as the idea that the seemingly barren land on which UCLA came to be situated was actually populated long before European settlers arrived. The story of how UCLA came to be is a long and serpentine one and this acknowledgement is a step in the direction of updating a narrative that was both incomplete and not widely known.

The Land

The UCLA Office of Equity, Diversity and Equality provides information about native peoples and UCLA’s connection to them. Living descendants of the Tongva continue to understand these lands as their ancestral homeland, contributing to what UCLA sees as its moral responsibility to acknowledge those who came before it.

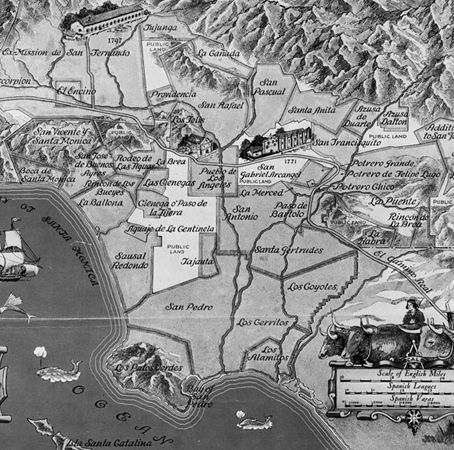

The land on which UCLA sits was colonized in a series of land grants and deeding of property under Western legislation; first, Tongva land was claimed through “discovery” by Spain. After gaining independence, Mexico issued the Rancho San Jose de Buenos Aires to Maximo Alanis. The first American title in 1866 went to Benjamin D. Wilson and W. T. B. Sanford, who eventually sold the land to the developer Arthur Letts. While not directly land dispersed through the Morill Act of 1862, which allowed for the creation of land-grant colleges in U.S. states, the financial backing of UC Berkeley made possible the purchase of land from the Janss brothers, upon which UCLA would be built.

In an unpublished work, Goeman, herself of Native American descent, discusses the transfer of over 17,400,000 acres of Indigenous land to these land grant colleges, meant to prepare a new class of laborers to build the nation. “These schools were built during the redemption period during reconstruction as whites worked to solidify racial hierarchies and established black codes simultaneously,” she writes. “Weaving these relational threads is necessary. It strengthens the braid.”

Who Are the Tongva?

The Tongva, known to have been in Southern California for thousands of years, were the people who canoed out to greet Spanish explorer Juan Rodriquez Cabrillo in 1542 upon his arrival off the shores of Catalina Island and San Pedro. Cabrillo declined their invitation to come ashore to visit. They inhabited the southern portion of what is today Los Angeles County, the northern portion of Orange County, and some western portions of both San Bernardino and Riverside Counties, living in autonomous villages comprised of related lineages with populations numbering 50 to 100 people and larger villages containing 300 people. When the first Spanish settlers arrived in 1781, there were dozens of such villages, some with as many as 400–500 huts, and a total population estimated to be as high as 10,000.

Portion of poster created by Tongva artist River Garza

The footprints and settlements of the Tongva people who inhabited the Los Angeles basin would become some of the landmarks of today’s city: a footpath through the mountains eventually became the 405 freeway; the largest Tongva village was in the area near downtown that became Los Angeles State Historic Park; a band of Tongva peoples settled along the Arroya Seco River. See the LA Times project Mapping the Tonga Villages of L.A.’s Past for more information.

Where Are the Tongva?

By 1840, only a few native villages remained in the Los Angeles area, as nearly the entire Indigenous population had been forcibly relocated to Spanish missions in San Juan Capistrano, San Gabriel and San Fernando. From 1846 to 1873, an estimated 80% of the California Indian population 80% of the California Indian population perished, many from violence and extreme conditions.

More than a century after this period of relocation, in 1994, the State of California officially recognized the Gabrielino-Tongva Tribe. As of 2008, over 1,700 people were documented as members of the tribe. Los Angeles now has the largest population of Native American and Indigenous people of any city in the United States and was a relatively early adopter (2017) of “Indigenous Peoples’ Day,” a movement that only started to gain serious momentum in 2014. To learn more about the original peoples of Los Angeles County and those from Indigenous diaspora, refer to the Mapping Indigenous LA website created by UCLA professors and researchers.

What Happened to the Tongva?

When asked what was the primary cause of the decimation of the Tongva population in the 19th century, Goeman does not hesitate. “Genocide. UCLA Department of History associate professor Benjamin Madley’s work, ‘An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846-1873,’ documents quite thoroughly how American vigilantism in the post-1850 period led to mass genocidal policies even by the states – all the way into the 1930s. The state was paying $25 for the scalp of native men and $5 for children.”

Even post-slavery, Goeman explains, native people were being sold to work out of Rancherias when they were arrested for vagrancy. Under the Act for the Government and Protection of Indians (1850), they were made to work until their fine was paid off.

“On the auction blocks in downtown La Plaza, which is where the Tongva were sold off, young women often achieved a higher rate, and thus we also have the concept of sex trafficking. Young women, people’s daughters and wives, were being forced into the brothels. And then men would come and try to get their daughters and it would lead to vigilantism [by local whites].

“When California became a state in 1850, around the time of the Gold Rush, there was this mass masculine movement west that caused massive violence within California – sexual violence, physical violence and the wiping out of native people from their lands. Seven-and-a-half million acres of land was supposed to go to native people; the money was embezzled. There were 19 treaties in California; they lost them. All of this while Indigenous people were facing the onslaught of military violence and vigilantism.”

This loss of land — or Indigenous lifeblood, as Goeman calls it — was not the end of the story. “Land continues to be demarcated as private property instead of a living relation. Our acknowledgement, our introductions and our knowledge systems reframe these landscapes.”

Acknowledgment as an Introduction

While the words now used to open UCLA events serve to help place UCLA within a greater historical context — and the Tongva as important players in that setting — Goeman sees it as much more than that. The Tongva, she says, do not want to be seen as fully in the past, but as re-emerging and having a presence in Los Angeles. “Part of the problems are what can happen when people write about Tongva people or any Indian people: it’s all about the past; it’s not about the present and a living culture, living communities or any of that. It’s what is termed ‘settler common sense.’ We read about Indians in the past and then look at how we developed and then we move on.”

The acknowledgement is really an introduction: a way for UCLA to recognize its position within the history of its physical and cultural environment but also in relation to an ever-evolving present.

According to Goeman, this process harms native people because it allows for the development of cities in which, for instance, native peoples’ gravesites are not protected — and many of those kinds of issues have been occurring in Los Angeles.

All of this supports Goeman’s view that the acknowledgement is really an introduction: a way for UCLA to recognize its position within the history of its physical and cultural environment but also in relation to an ever-evolving present. The more the acknowledgement circulates, she says, the more it and others like it become part of the fiber of our land grant institutions throughout the country.

Goeman writes, “The introduction is an anticolonial tool in this instance; it is not an apology for the past or a single thread to a past, it weaves a future forward. The introduction is a mechanism for the beginning of not only acknowledging your place in the world but also one of creating Indigenous and allied networks. It reframes landscapes and our relationships to them. The introduction is a first step in organizing Indigenous belonging.”

She elaborates on why the acknowledgement is not an apology. “An apology means nothing unless you have action behind that particular apologetic mode. You can’t apologize and still be doing the harm, whether that’s at Standing Rock, where they just had a huge oil spill, or the selling off of BLM [Bureau of Land Management] land, which is land that has never been ceded, or holding people as political prisoners for protecting their land base and sacred sites. You can’t really have an apology while you’re still continuing those behaviors.”

Some states are going further than land acknowledgements. Oregon has introduced a bill that provides that public universities and community colleges must waive all tuition and fees for enrolled students who are members of Native American tribes historically based in Oregon. The bill also provides that public universities and community colleges must charge no more than resident tuition for enrolled students who are members of Native American tribes not based in Oregon.

Goeman feels that this type of substantive step needs to happen throughout the country. “There are some universities that have particularly close relationships with native peoples, like the Arizona universities and Minnesota, but in the UC system we’re also somewhat ahead of the game. Others are trying; sometimes people just don’t know how.”

One important step is rescuing the native language from extinction. With the numbers of Tongva people so low, it was at risk of being lost, and, as noted by linguist David Pello, “Language is ethnicity. Language identifies you; it informs listeners who you are.” UCLA linguist Pam Munro has been teaching Tongva language classes in a San Pedro classroom for 15 years in an effort to save the language – and with it, a major part of Tongva culture. Her efforts, together with UCLA’s introduction, will help ensure that an important part of Los Angeles history will not be forgotten and will help shape its future.