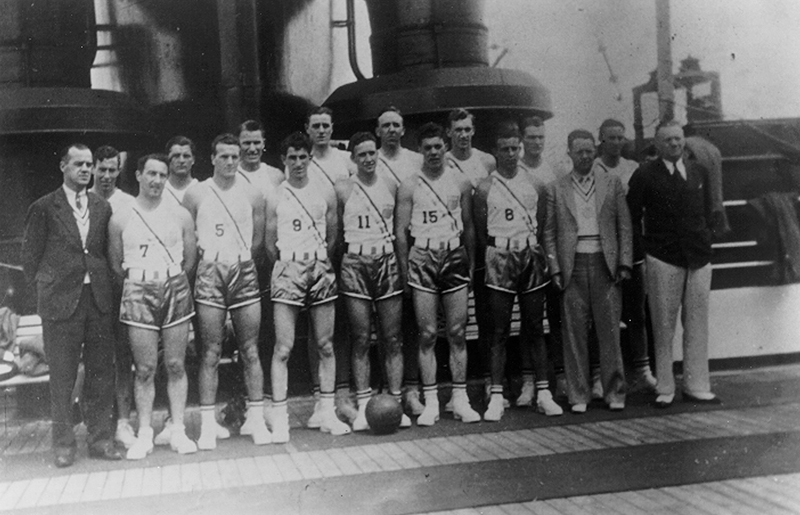

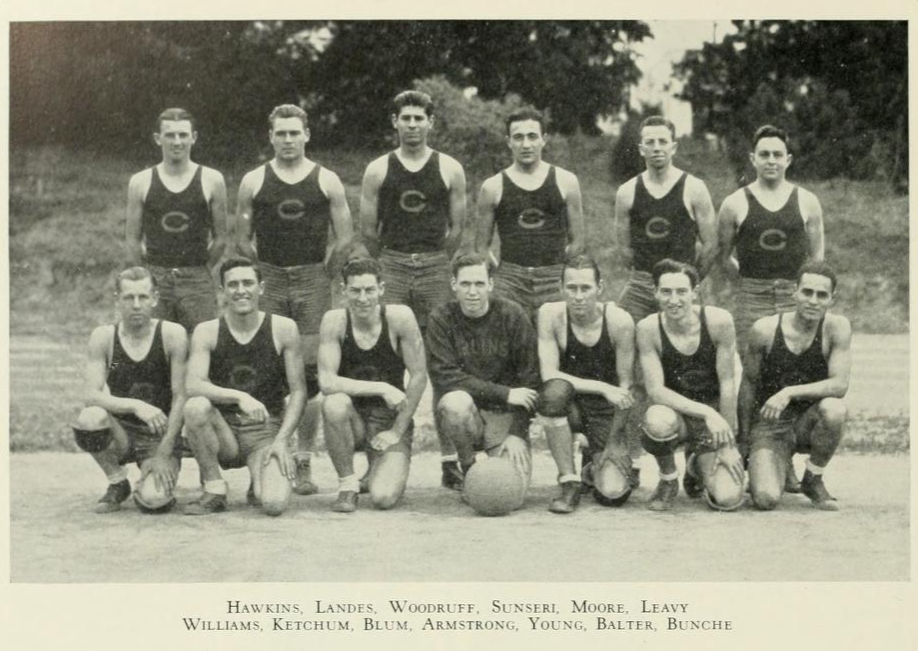

The 1936 U.S. Olympic Basketball team, featuring five former Bruins

When we think of UCLA Basketball and its prominent place in sports history, we naturally flash back to John Wooden and the championship teams of the 60s and 70s, featuring Lew Alcindor ’69 (now Kareem Abdul-Jabbar), Bill Walton ’74 and so many other all-time greats. We might recall other excellent teams and players, such as the 1995 NCAA champions or early standouts like Kenny Washington and the great Jackie Robinson. But we probably don’t associate UCLA Basketball with the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, Germany – the “Nazi Games” in which Jesse Owens starred, to the chagrin of dictator Adolf Hitler and his Aryan supremacist followers.

In a new book, “Games of Deception,” author Andrew Maraniss examines the invention and early years of the game of basketball, culminating in its inclusion in the 1936 Summer Olympics. Foreshadowing the dominance that UCLA would eventually exhibit in amateur basketball, that first U.S. Olympic basketball team included five former UCLA players who had hooped together on an amateur team after college, and who would help win Olympic gold in Berlin. Through extensive research – including new recollections from some who were actually there nearly 84 years ago – Maraniss gives us a vivid picture of what life was like for minorities, in the United States as well as in Nazi Germany, before, during and after the Games. He details the way the Nazis attempted to hide their terror campaign against minorities – in particular, Jews – via a propaganda campaign that, for Hitler, was the main benefit of hosting the Games.

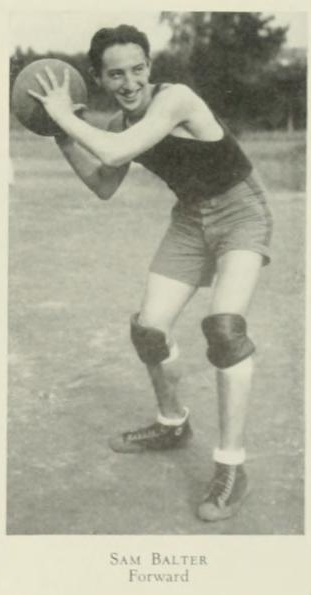

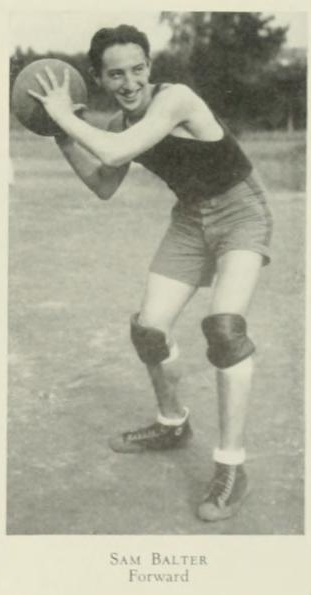

Sam Balter, pictured in the 1927 UCLA yearbook

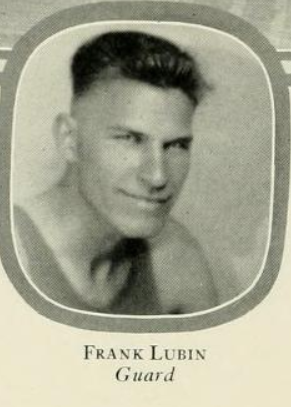

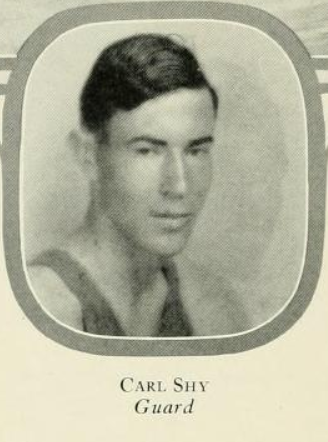

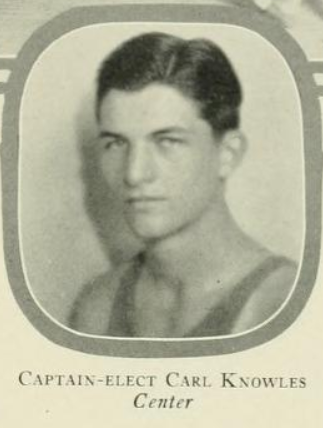

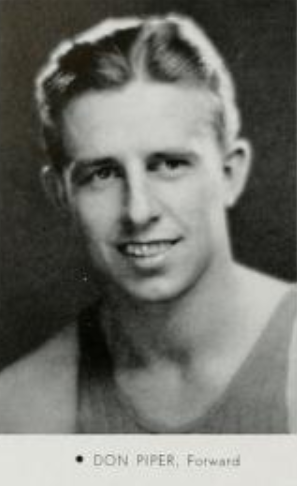

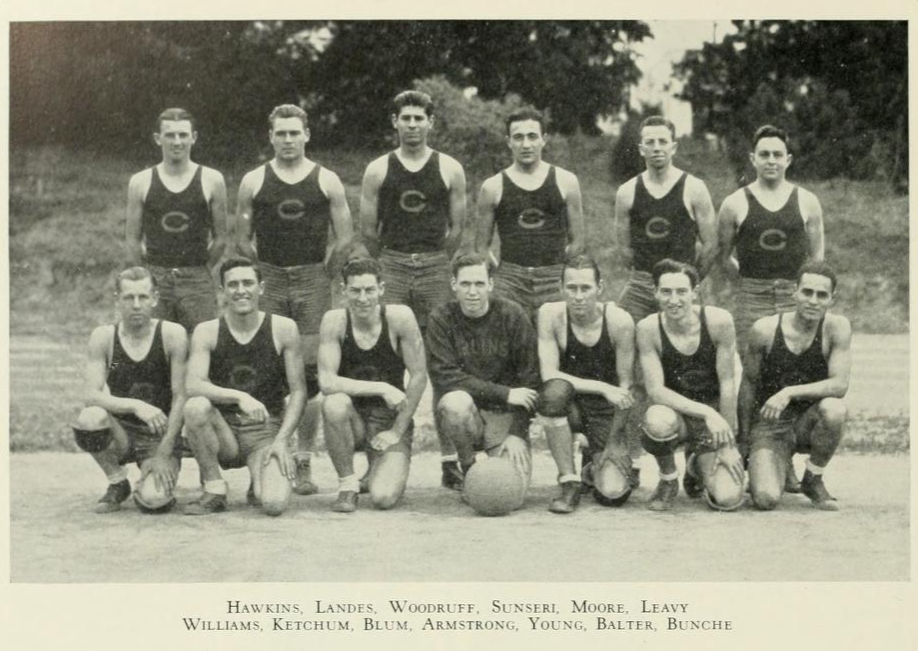

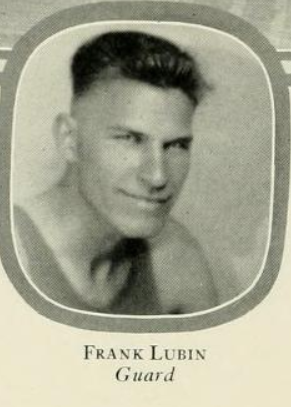

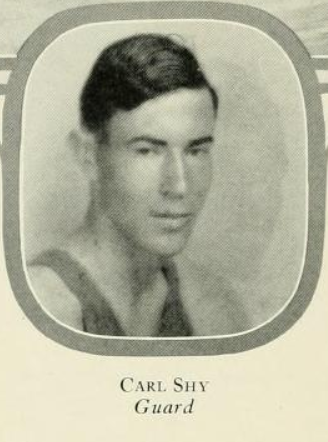

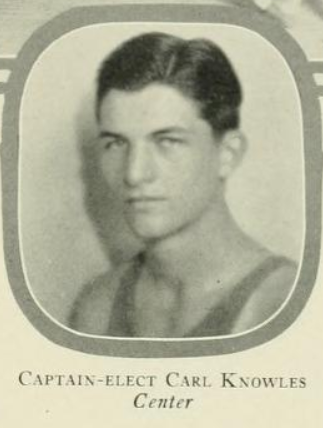

The U.S. basketball roster was made up of players from the two amateur teams – one representing Universal Studios, the other an oil refinery in Kansas – that had made it to the finals of the Olympic qualifying tournament (plus one collegiate player). The five former UCLA players on the team were Sam Balter ’29 (English), Frank Lubin ’31 (political science), Carl Knowles, Donald Piper and Carl Shy. All played on the Universal team, set up by Universal Pictures creator Carl Laemmle, a sports enthusiast.

Frank Lubin, 1930 UCLA yearbook

The public relations value of the Games was dealt a severe blow by the African American athletes who excelled there. Maraniss writes, “While the Nazis fiercely resisted allowing Jewish athletes to compete for Germany in ’36, there were 18 black people on the U.S. team, including the great sprinter Jesse Owens. [In the 200-meter dash, Jackie Robinson’s brother Mack won the silver, four-tenths of a second behind Owens.] In all, African American athletes would win fourteen medals in Berlin. At an Olympics designed to showcase a white supremacist regime, black Americans were far and away the stars.”

Carl Shy, 1930 UCLA yearbook

There were no black players on the basketball team, however. This was because the manner in which the Olympic basketball squad was selected would have meant including a whole team of black players as half the contingent of the U.S. squad, which, says Maraniss, “was unthinkable to the white men in charge.”

Carl Knowles, 1930 UCLA yearbook

Despite the results of the athletic competition, the “deception” alluded to in the book’s title appears to have been successful in letting the Nazis continue their atrocities and prepare for war while presenting a sparkling, organized, open and tolerant city and society. Not everyone was taken in, however.

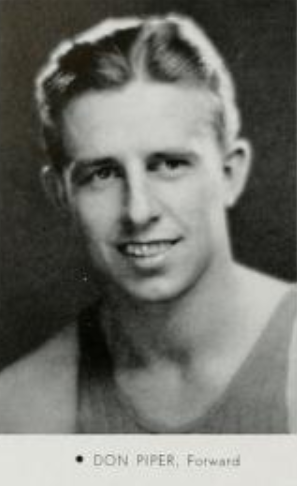

Donald Piper, 1933 UCLA yearbook

“Balter’s concern about the Nazis’ true intentions for the Olympics had only grown stronger during his time in Berlin,” writes Maraniss. “The whole affair, he knew, had been one huge sales convention promoting the product of Nazism and its ‘byproducts of paganism, militarism, anti-Semitism and Fascism.’ Worst of all, Balter felt, most of the visitors to the Games had bought what the Nazis were selling.”

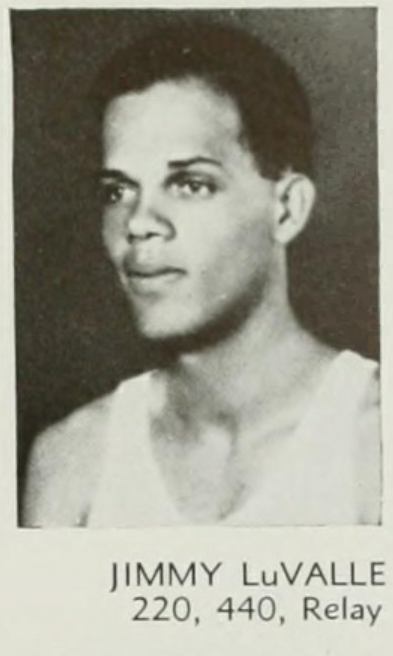

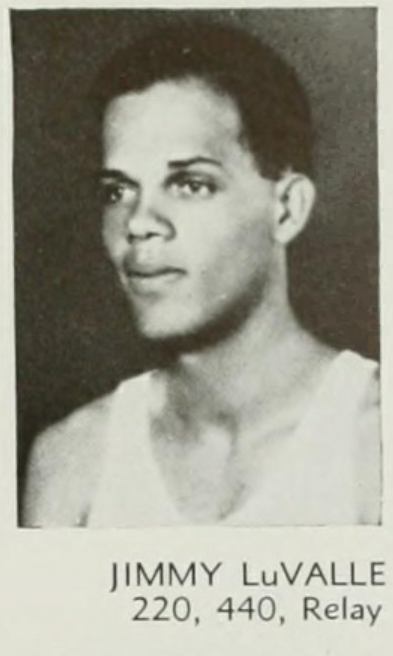

James LuValle, 1934 UCLA yearbook

James LuValle ’36, M.A. ‘37, who ran the 400-meter race, took note of the contrast between the athletes from all the nations gathered on a field on opening day and the thousands of uniformed Nazis lining the road to the location. “On one side I had 55 nations who were there to see who could run the fastest, who could jump the highest, who could dive with the most beauty,” he said. “On the other side, we had over 50,000 ready to go to war that day.”

Since Olympic rules only allowed for seven players to suit up for a game, the U.S. basketball team was split into two seven-man squads who alternated games. The Americans found the road to the finals a smooth one (certainly smoother than the muddy outdoor court on which the final was played). After winning in a forfeit over Spain, the squad nicknamed the “Sure Passers” beat Estonia 52-28, with Lubin scoring 13 points, Shy 10 and Balter seven. The other seven, called the “Wild Men,” beat the Philippines, 56-23 in the quarterfinals. The Sure Passers then defeated Mexico 25-10 in the semis, with Balter scoring 10 and Lubin nine.

In the sloppy final, the Wild Men beat Canada 19-8 and the U.S. had won the first gold medal awarded in Olympic basketball. A few days later, the basketball victors and their American Olympic teammates returned stateside, where they were soon reminded of the segregation that existed in their country. Maraniss relates this story involving Balter and a UCLA legend who tried to visit him.

“On his way home, Sam Balter was sitting in his D.C. hotel room one afternoon when the phone rang; it was a woman at the front desk telling Balter he had a visitor, an old teammate from UCLA who wanted to congratulate him. Balter said to send him on up. The woman replied that she couldn’t; they didn’t allow Negroes past the lobby. Balter was embarrassed and humiliated as he met a gracious Ralph Bunche [‘27] in the lobby.”

According to Maraniss, “Even as he planned for war, Hitler also imagined a new future for the Olympic Games. With Tokyo scheduled to host the Games in 1940, he intended for the Olympics to return to Germany in 1944 and remain there forever. By 1937, his architect had drawn up plans for a massive 400,000-seat stadium in Nuremberg. This would be the center of Hitler’s new world order; this is where white people would come every four years to compete. No black, brown or Jewish athletes allowed.”

Fortunately, of course, Hitler was stopped and this dystopian world never came into being. Society started the slow, winding path toward civil rights for all and UCLA continued to produce ground-breaking students and athletes, including Don Barksdale ‘47, the first African American basketball player to be named NCAA All-American, the first to play on a United States men's Olympic basketball team and the first to play in a National Basketball Association All-Star Game. The year after he graduated, John Wooden arrived in Westwood. But that’s another story…

The 1927 UCLA Basketball team, with Sam Balter and Ralph Bunche front row, right