|

|||

|

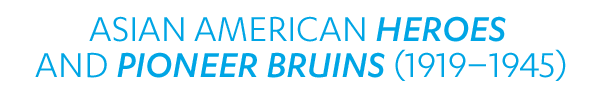

The story of UCLA has been written by 100 years of brilliant, diverse and determined students. Between 1919 and 1945 Asian American students at UCLA blazed a trail of achievements, fighting against policies of marginalization and discrimination, even internment. While many details of these individual lives have been lost to history, stories have been recorded of Bruins who created opportunities at UCLA and beyond. |

|||

|

|||

|

In the early 1900s Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Pilipino and South Asian immigrants came to America in search of better wages and a brighter future. These immigrants mainly settled in Hawaii, a U.S. territory in 1898, and along the West Coast. At the same time, restrictive laws were passed prohibiting citizenship, land ownership and other immigration restrictions. The Vermont Avenue campus, known as UC's Southern Branch, opened in 1919. From these early days, Asian students, mainly born abroad, were represented among the student body. But jobs equal to their education were scarce in America, and many returned to their parents’ homeland, or found themselves limited to jobs in agriculture or the service industry. Melany de la Cruz-Viesca, assistant director of UCLA’s Asian American Studies Center, says, “There was a pressure to prove themselves, to be successful. It was isolating and alienating to be one of a select few. There’s tension and pressure for first-generation college students, or first generation immigrants, to preserve their culture and history for future generations.” One early Bruin, Kazuo Kawai was born in Japan. His father’s work with a Christian ministry brought the family to Los Angeles. Kawai attended UCLA in the late 1920s, transferring to Stanford and earning his B.A., M.A. and Ph.D. In 1926, he wrote “Three Roads and None Easy,” a record of his conflicted feelings about being born in Japan, growing up in America and not feeling accepted by either. Considering his options after graduation, he chose to study Far East history and to become a cultural interpreter, rather than trying to fit in. Kawai returned to UCLA in 1932 as an instructor of history and geography. He was visiting his parents in Japan when World War II began, and was not permitted to return home. He spent the war years in Japan working on the staff of the Nippon Times, Tokyo’s English language newspaper. After the war he returned to the United States and settled at Ohio State as a professor of political science. On campus social organizations created networks that helped students stay in touch and share opportunities after college. De la Cruz-Viesca explains, “UCLA promoted opportunities and provided space for students to organize along social, cultural and political lines. These deepened relationships carried over after college and allowed students to become more successful.”

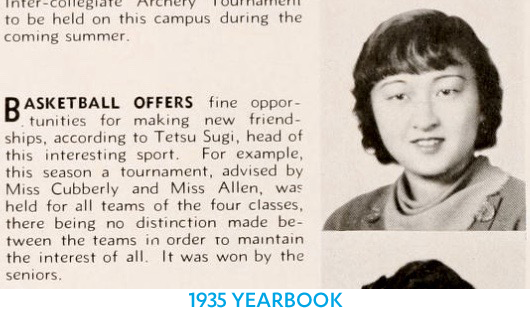

A 1927 yearbook photo shows The Cosmopolitan Club, a national social club that fostered intercultural and international understanding. The club hosted speakers, international singing and dancing performances and social dinners. An article in the November 1927 Daily Bruin article notes that there are students on campus from 40 countries, and that The Cosmopolitan Club “brings types from every land into a social and convivial group.”

In 1928 a group of Japanese women at UCLA wanted to join a sorority but were denied entry into the University Greek system. With support from the Dean of Women, Helen M. Laughlin, they started Chi Alpha Delta, and were recognized as a sorority on April 5, 1929. Around the same time, a Japanese Bruin club formed, and the two groups met for dances and dinners. Now in their 86th year on campus the current website says, “Charter members recognized a need to promote friendships, communication, and social activity among University women of Asian descent, as well as a desire to encourage school service and school spirit.” |

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

In the early 30s, America was in the midst of the Great Depression, further limiting opportunities for many students. Some graduates turned to unskilled jobs, like Victor Pacifico Magpiong ’32 and George Iel-Choong Kwon ‘32, past-president of the Cosmopolitan Club, who both graduated from UCLA in 1932. After graduation, Magpiong, with a degree in Political Science, worked as waiter in a café, and Kwon, with a degree in history and education, found work as a grocery store clerk. The entrepreneurial pair wrote and published a cookbook “Oriental Culinary Art: An Authentic Book of Recipes from China, Korea, Japan and the Philippines.” Copies are still occasionally available, one auction website says, “Possibly the second Asian-American cookbook ... and the first to include Korean and Filipino recipes.”

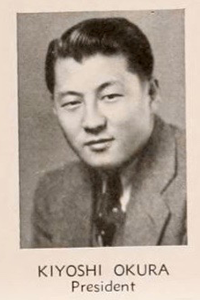

Kiyoshi Patrick Okura ’33, M.A. ’35 was the first Japanese American to play varsity baseball at UCLA and a founding member of the Japanese American Bruins Club. After earning his master’s degree he was frustrated by the difficulty in finding suitable work. He challenged the city of Los Angeles’ segregationist hiring practices and succeeded in becoming the city's first Japanese American working for the Los Angeles Civil Service Commission. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, he was accused of using his position to run a spy network and forced to resign, although charges were later dropped. In 1941, he was sent to the Santa Anita Park internment camp, where he and his wife, Lily, lived in an 8-by-8-foot tack room in a horse stable. He was able to leave internment when Rev. Edward Flanagan, the founder of Boys Town, sponsored about 50 Japanese American families and brought them to Omaha, Nebraska. Okura became the Boys Town's staff psychologist, and later worked for the National Institutes of Health, creating programs for minority communities. Okura became a leader of the civil-rights organization, Japanese American Citizens League. He was honored as a Japanese American of the Biennium in 1978, and by the emperor of Japan in 1999. In 1988, President Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act offering a formal apology and financial compensation for surviving victims. The Okuras used their reparation funds to cofound the Okura Mental Health Leadership Foundation to promote leadership, research and training in human services. They donated their papers to UCLA , a testament to lives of service.

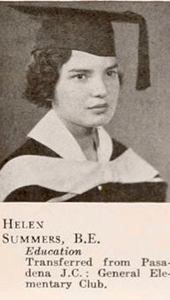

Helen Agcaoili Summers Brown, ’37, M.A. ’39 was born in Manila to Trinidad Aqcaoili and George Summers. She transferred to UCLA from Pasadena City College, and is credited as the first Pilipina to graduate from UCLA. She married her college sweetheart, William Brown, who also attended UCLA. Brown was a teacher and counselor for the Los Angeles Unified School District, where she was an advocate for bilingual education and cultural diversity awareness. Based on her personal experience researching her identity, she realized there was a lack of resources about the history and people of the Philippines. She began collecting books and magazines, and making these materials available to others. In 1985 she opened Pilipino American Reading Room, now the Filipino American Library, known as "Helen's library," in donated space in the basement of the Filipino Christian Church, later moving to a larger space on Temple Street. She is remembered as a pioneer in preserving and promoting the history of the Pilipino-American community. In 2011 the Pilipino Alumni Association honored her with a posthumous special recognition as Distinguished Alumni of the Year. |

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

In December of 1941 the United States entered World War II. Students across the university were impacted in countless ways, but for students of Japanese heritage, the 1940s held a unique set of challenges. |

|||

|

|||

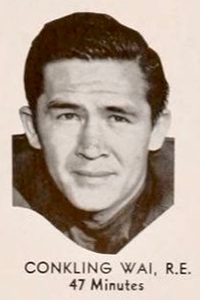

The Wai brothers–Francis, Conkling and Robert–were born in Hawaii. All three played football for the Bruin, Francis and Conkling were part of the memorable team that included Woody Strode and Kenny Washington. Wai graduated in 1940 with plans to join his father in the finance business, but instead joined the Hawaii National Guard and was soon called to active duty.

Although few Asian Americans were allowed to serve in leadership roles, Wai was commissioned as an officer. Captain Wai served in the 34th Regiment of the 24th Infantry Division and was killed in 1944. In 2000, following Congressional review of the war records of Asian American soldiers during WWII, Wai was posthumously awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. Wai was inducted into the UCLA Athletics Hall of Fame in 2014 for football, basketball, track & field and rugby.

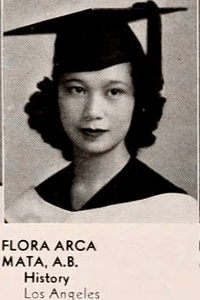

Flora Arca Mata ’40 was born in Hawaii, moving with her family to a large Pilipino community in Stockton where her parents and siblings worked in the fields. Mata was able to attend college with the financial help of an older sister. When Mata graduated from UCLA she could not find a teaching job. The Dean of Women offered to help, with the caveat that any job would have to be in Hawaii. Mata recalled in an interview with author Dawn Bohulano, “Why is it that America would educate the minority and not give them an opportunity to use this education?” Mata worked as a maid and her husband worked as a chauffeur until they moved to the Philippines to teach. They were in the Philippines during WWII, returning to Stockton after the war. In Stockton she answered an ad for a teaching job, and was hired first as a substitute, and then as Stockton’s first Asian American full-time teacher. Mata retired in 1978, and continued substitute teaching into her 80s. Her daughter has said, “My mother imbedded in us the idea that you cannot hold hate. If you want to change the thinking of people, go into the classroom.” In 2013 Brown’s memory was honored by Congressmember Jerry McNerney, “I urge my colleagues to join me in recognizing the barriers Ms. Mata shattered and the road she paved.” |

|||

|

|||

On Dec. 7, 1941, Japanese forces attacked Hawaii’s Pearl Harbor and the United States entered World War II. On Feb. 19, 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order No. 9066, authorizing the forced relocation of more than 120,000 Japanese Americans living on the West Coast and sending them to internment camps. First and second generation Japanese students at UCLA and across the “Evacuation Zone” were no longer welcome on campus. On April 29, 1942 the Daily Bruin’s headline proclaimed the final day at UCLA for 175 Japanese American students. UCLA students and faculty hosted events to raise funds, toys and books for their former classmates. Dr. Earle Hedrick chaired a committee asking other schools, outside the evacuation zone, to accept UCLA students. |

|||

|

|||

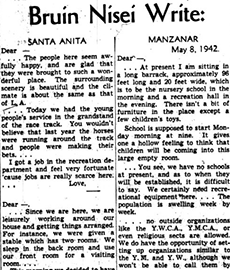

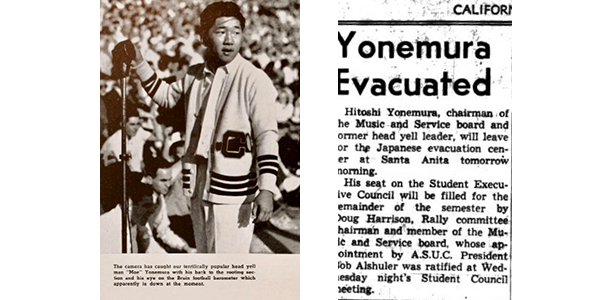

UCLA’s President Sproul recommended to California’s governor that these students receive tuition assistance. 142 students received refunds. The Daily Bruin printed letters students received from their peers at Manzanar and Santa Anita. Hitoshi “Moe” Yonemura was a popular student who was elected junior class treasurer. In 1942 he was UCLA's head yell leader, served in student government and was part of the ROTC program at UCLA. In March of 1942 Yonemura was elected senior class treasurer. |

|||

|

|||

| By May, he was uprooted and sent to Manzanar Internment Camp. From Manzanar, Yonemura enlisted in the U.S. Army and became an officer with the Cannon Company of the 442nd Brigade in World War II. 2nd LT Yonemura was killed in action in April 1945. For his bravery in action he was awarded the Silver Star and Purple Heart. In 2003, the UCLA Class of 1942 60th Reunion Committee established a scholarship in his name to honor his “legacy of service, leadership and perseverance.” More than 260 UCLA students, faculty and alumni were killed in World War II, among them many Asian-American students who fought for the United States.

James Yamazaki ’39 was born in California; he earned a B.A. from UCLA in 1939 and an M.D. from Marquette University in 1943. Yamazaki received his Army commission one week before Pearl Harbor, and served in the U.S. Army, becoming a prisoner of war. After the war, he wrote 100 letters to hospitals searching for a residency, and was finally accepted at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Later, he traveled to Japan with a team investigating the effects of radiation on children in Nagasaki and Hiroshima, Children of the Atomic Bomb. He returned to Los Angeles where he joined UCLA’s new pediatric department and became a professor of pediatrics. He received the Professional Achievement Award from UCLA Alumni in 1996.

Akio Hirashiki Yamazaki, James Yamazaki’s wife, also went to UCLA where she served as president of Chi Alpha Delta. As reported later in the LA Times, on Dec. 10, 1941, she and other Japanese-American leaders on campus issued a statement to the student newspaper saying that none had ever "known loyalty to any country other than the country of our birth. . . . Individually and collectively, we plead that our friends will accord us the same impartiality and tolerance which they have shown us in the past." She was only a few credits short of graduation when she was made to leave school for Santa Anita Park’s internment camp. In 1992, as part of events commemorating the 50th anniversary of the mass removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans she was awarded her bachelor's degree in dietetics at a special ceremony at Royce Hall.

UC Regent Eddie Island was quoted in an LA Times article about the event, "Fear is a powerful thing. And when it is put to an evil purpose as it was in this case, we owe a sense of profound regret, profound sorrow, that our country was off track. Today, we can rectify that in some very small way." In May 2010 UCLA, and all of the University of California campuses, honored these students with a ceremony and special honorary degrees with a Latin inscription translated as "to restore justice among the groves of the academy." The UCLA Asian American student experience of 1919-1945 is a reflection of that time in history. UCLA’s de la Cruz-Viesca says, “These students were often considered to be foreigners. Many were discriminated against while some were able to cross over by participating in sports or debate. This spectrum of experience forms the base of the Asian American identity that you begin see in the 1960s and 70s.” | |||

|

|