|

||||

|

||||

|

UCLA currently ranks as the 5th most LGBTQ-friendly college in America [source: College Choice] based on the strength of its organizations, events, outreach and programming. This reflects a tradition of activism and organizing for social justice by UCLA students, staff and faculty and a commitment to supporting scholarly research that challenges the status quo.

UCLA’s legacy of progress in the movement for equal rights and protections for the LGBTQ community has been driven by its participants. Albert Aubin, Ed.D. ’71, a pioneer for social justice, has been an active force in the UCLA community since he was a graduate student in the 1970s. He recently retired from the UCLA Career Center after 40 years of service. He recalls that in the late 1980s/early 1990s the UCLA campus was a very different place that, he felt, needed increased emphasis on the value of diversity. He says, “Historically the LGBTQ community was not visible. We all want to feel safe and secure.” As early as the 1950s, UCLA professor Evelyn Hooker’s research studies challenged stereotypical perceptions of gay men. In the 1970s, the national gay liberation movement was reflected on campus in the establishment of UCLA’s Gay Student Union (GSU), one of the most active gay student organizations on a California college campus at that time. The GSU held UCLA’s first Gay Awareness Week In 1974 with guest speakers, lectures and a dance party. The 1980s ushered in a new era with the AIDS epidemic and the 1993 "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" law, forbidding gays, bisexuals, and lesbians from serving openly in the United States military. During this time, the UCLA community continued to organize to make the campus a more fair and welcoming place for all. While students had created a gay community on campus, faculty and staff who chose not to conceal part of their identity often faced reprisal and discrimination. Aubin says, “We were not included, you could legitimately discriminate.”

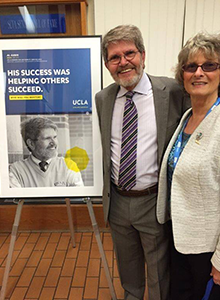

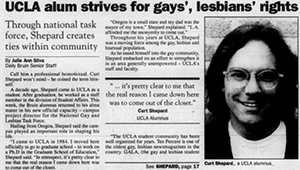

Curt Shepard, Ph.D. ’89 is a lifelong activist who earned his Ph.D. in psychology in 1989 and worked for UCLA Student Affairs in the 1990s. Currently serving as chief of staff of the Hammer Museum, he spent nearly a decade at the L.A. LGBT Center. He recalls being unable to include a gay question on the Freshman Survey, a questionnaire on the thoughts of incoming students. He was also “talked out of doing a dissertation topic on a queer subject. At the time, there was big resistance.” UCLA students tried, and failed, to have the ROTC removed from campus since students who came out publicly would have to leave the program and lose their scholarship support. Graduate students were concerned about future employment; assistant professors were concerned they would not get tenure. In 1989, Student Affairs’ staff members attended a one-day diversity training facilitated by Lillian Roybal Rose. The training presented Shepard with a personal opportunity that would become a catalyst for change. Staff members met in small groups for an intense day of training. At the end of the day, Roybal Rose created an imaginary line down the center of the room and asked participants to cross the line if they had been a target of discrimination. “She went through a list: age, disability, race, religion,” Shepard recalls, “The last one was sexual orientation. In the moment, I decided to cross the line. I was the only one in my group who did. You were asked to stand there and look people in the eye. It was very emotional.” People had crossed the line in other sessions as well, and they decided to organize a meeting for gay and lesbian faculty and staff. Shepard says, “People were uncomfortable meeting on campus, so our first meeting was off campus, 35 people attended. The second meeting had 60.” The next meeting was held on campus, 100 people attended, and guests Sheila Kuehl ’62 and Torie Osborn spoke. These meetings became the UCLA Lesbian and Gay Faculty/Staff Network. Aubin says, “We were fortunate to have a very supportive chancellor [UCLA Chancellor Charles E. Young] who attended our meetings and Assistant Vice Chancellor Tom Lifka who was an advocate and helped to pave the way.” Chancellor Young had been one of the first university leaders to direct departments to not discriminate based on sexual orientation in the 1970s. Shepard, Aubin and UCLA Director of Admissions Rae Lee Siporin formed a steering committee that became the Chancellor's Advisory Committee on Lesbian and Gay Community, now known as the Chancellorial Advisory Committee on LGBT. The committee worked for, and achieved, domestic partner benefits for faculty and staff, effective in 1998, and a non-discrimination policy.

In the early 1990s, Shepard conducted a campus-climate survey through the Student Affairs Information and Research Office (SAIRO). The survey provided data that backed up anecdotal stories of discrimination and harassment faced by members of the on LGBT community. Shepard felt a center would give UCLA a much-needed resource, and began developing a proposal to start a resource center. While it took several years to establish a center at UCLA, in the meantime the proposal provided a template for LGBT centers at campuses around the country. In 1993, Shepard left UCLA and went to work for the National Gay & Lesbian Task Force (NGLTF). He says, “It became my job to do campus organizing.” Shepard, working with Charles Outcult and Felicia Escalta, produced a how-to manual on establishing a resource center, the first policy publication of NGLTF. Aubin says “Curt’s work laid the foundation nationally. In addition to research and application, the proposal included details on how to make it happen.” UCLA’s Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender (LGBT) Resource Center was established in 1995. The current center supports more than 20 student groups and houses the student-run Rae Lee Siporin Library, and the David Bohnett CyberCenter for student’s information technology needs. The 21st century has heralded new gains for the LGBT community, and UCLA has continued to make steady progress. The Williams Institute, an institution in support of LGBT academic programs, was founded at UCLA in 2001 through a grant by Charles R. "Chuck" Williams. The Williams Institute focuses on legal research, policy analysis and leadership development, including such topics as work discrimination, adoption policies and public health. UCLA established an undergraduate minor in lesbian, gay, and bisexual studies in 1997, the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Studies Program and is currently working on a proposal for the first Ph.D. program in LGBTQ Studies.

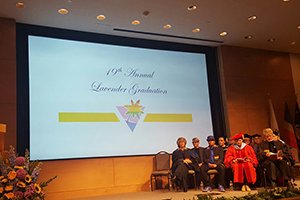

In 1998 Dr. Ronni Sanlo, a former director of the Center, established the Lavender Graduation, a demonstration of the now well-established community. Aubin says “I love seeing the families. It’s good for parents to see the support from the university.” Both Aubin and Shepard, along with other community leaders, are honored with graduation awards in their name - the Curtis Shepard UCLA LGBT Leadership Award and the Al Aubin Service Award. This year's Lavender Graduation is taking place on Saturday, June 17, from 1-3 p.m. at Korn Convocation Hall in the Anderson School of Management. While a great deal has been accomplished, Shepard says it is not a time for complacency, “People are afraid. We’re not removed from the current threats; it can be taken away from you. Don’t be complacent. Be brave, live your truth.” Aubin, though retired, continues to work with the UCLA community. He says, “Celebrating the 20th anniversary of the Center was such a warm feeling. We had a common goal and each of us brought our expertise, the power was in bringing them together. Now we have great diversity representation, but we still need inclusion. We all need support; you don’t have to do it alone.” |

||||

|

|